The Case for EFTA

Daniel Hannan MEP

About the Author

Daniel Hannan was elected a Conservative MEP for South East England in 1999, and re-elected in top position in 2004. He is a leader writer on The Daily Telegraph and a columnist on The Sunday Telegraph and the German newspaper Die Welt. He sits on the European Parliament’s Constitutional Affairs Committee, and was the first person in Britain to call for a referendum on the EU constitution. His publications include A Treaty Too Far, The Challenge of the East, The Euro: Bad for Business, A Guide to the Amsterdam Treaty and What if Britain votes No? He speaks French and Spanish, and has been a member of the Bruges Group since 1991.

“Of course, Britain could survive outside the EU... We could probably get access to the single market as Norway and Switzerland do...”

The Rt Hon Tony Blair MP, 23rd February 2000

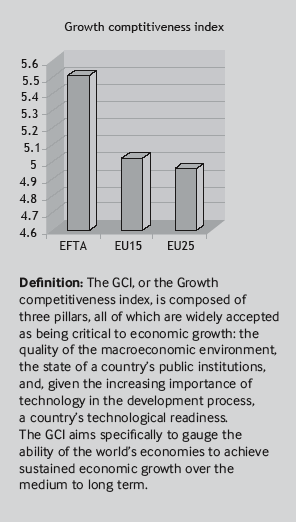

You would have thought that the case for the European Free Trade Area (EFTA) didn’t need making. After all, the four EFTA members, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, are measurably better off than the 25 EU members. Just look at the statistics.

State

GDP PER CAPITA (USD)

Norway 48,400

Switzerland 43,900

Iceland 36,300

Liechtenstein 30,000

EU 15 (pre-enlargement) 27,500

EU 25 21,800

Source: OECD

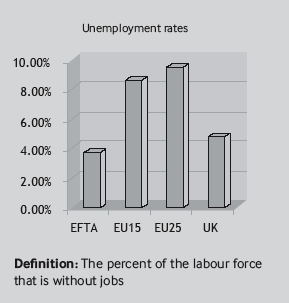

People in EFTA are more than twice as rich as those in the EU. They also enjoy lower inflation, higher employment, healthier budget surpluses and lower real interest rates. Interestingly, they also export more per head than EU states, selling $16,498 per capita to overseas markets – the highest ratio in the world.

Since British Euro-philes have always based their argument on economic necessity, EFTA pretty well demolishes their case. Here, after all, is empirical evidence that countries which participate in the European market without subjecting themselves to the associated costs of membership are wealthier than full EU members.

Nor is this coincidence. The EFTA states have found a way to have their cake while guzzling away at it. They are not identical, of course; each one has struck its own accord with Brussels. In particular, there are important differences between Switzerland, whose relations with the EU are mediated through sixteen sectoral treaties, and the other three, which are members of the European Economic Area (EEA). But some things can be said of all four of them.

The EFTA states participate fully in the so-called Four Freedoms of the single market — free movement, that is, of goods, services, people and capital. But they are outside the Common Agricultural Policy. They control their own territorial resources, including fish stocks and energy reserves. They administer their own frontiers and admit whom they choose onto their territory. They settle their own human rights questions. They are exempt from a good deal of EU social and employment law (all of it in the case of Switzerland). They are able to negotiate free trade deals with third countries. They pay only a token contribution to the Brussels budget. Oh yes, and they’re all sovereign democracies.

Not a bad deal, eh? The vital difference between the EU and EFTA is that the former is a customs union while the latter is a — well, a free trade area. In other words, EFTA concerns itself with goods and services that circulate among its members, not within them. As an Icelandic trade official put it: “EFTA doesn’t busy itself with behind-border issues the way the EU does”. Critically, EFTA states are able to sign commercial accords with non-European states that go beyond what the EU has been prepared to negotiate. In practice, EFTA and the EU are usually treated as a single bloc by third countries, for reasons of practicality. But where the EFTA states feel that the EU is being unduly protectionist, they can always go further. They have, for example, signed comprehensive free trade accords with Singapore, South Africa, and South Korea and are currently negotiating one with Canada. In other words, EU trade deals are, for EFTA, a minimum floor on which they have the option of building.

The difference between the two bodies can be inferred from their institutions. The EU, which seeks to regulate economic activity across its entire territory, requires gargantuan enforcement machinery. EFTA, being a trade association, does not. Its regulatory bodies are the EFTA Surveillance Authority, which is the equivalent of the European Commission, and the EFTA Court, analogous to the European Court of Justice (ECJ). Both institutions are sited near their EU counterparts in, respectively, Brussels and Luxembourg. But they have remained slim, efficient agencies. The EFTA Surveillance Authority employs fewer than 50 staff, compared to the 18,000 who work at the European Commission. The EFTA Court has just 15 officials, as against 1,800 in the ECJ.

EFTA comes close to realising the dispensation that most British voters always wanted from Europe: free trade without unnecessary regulation or political union. Its rude prosperity is embarrassing to British Euro-sophists, who have been telling us for 30 years that the EU is vital to our economic survival. Naturally, Eurocrats have evolved a series of arguments to disparage the EFTA states. Since this is likely to become a lively debate in Britain in the coming years, it is worth looking at these arguments in turn. I shall try to cover all the assertions habitually made by supporters of the EU.

The EFTA states have to assimilate thousands of EU laws over whose drafting they have had no say.

This is the so-called “fax diplomacy” argument: because EFTA states are obliged to adopt several single market measures, their lawmakers are portrayed as sitting next to their fax machines waiting for the directives to come from Brussels. It is certainly true that the three EEA states, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, have to apply a number of single market regulations. But these tend to be technical in nature, and are limited to a clearly defined part of their economy. Since the EEA was born in 1992, Norway and Iceland have each adopted around 3,000 EU legal acts (the figure is lower in Liechtenstein, which joined later). But few of these rules were important enough to need legislation in those countries: the 3,000 legislative acts have required fewer than 50 parliamentary statutes in the Norway’s Storting and Iceland’s Althing. They deal with such matters as the correct way to list ingredients on a ketchup bottle; they do not tell the Norwegians and Icelanders what to tax, where to fish, whom to employ or what surplus to run. And it is not true that the EEA states have no say over these rules. There are formal consultation mechanisms built into the EEA accord. Oddly, those who point so excitedly to the 3,000 Euro-laws adopted by Norway neglect to mention the 18,000 that Britain has had to accept over the same period. In any case, if the Norwegian option is regarded as undesirable, there is always the Swiss option: Switzerland, being outside the EEA, relies instead on bilateral treaties with the EU, synchronising its regulations with its neighbours only when it wishes (which, being an exporting country, it often does). One final point, which is almost always overlooked. The founding charter of the EEA, the Lisbon Treaty, enshrines the EU’s jurisdiction as it stood on 2 May 1992. It provides no mechanism to impose on Norway, Iceland or Liechtenstein the extensions of EU power that have happened in subsequent treaties, notably in the fields of employment law, social policy and justice and home affairs. It is up to these countries to decide whether they wish to alter their own law to keep pace with the EU in these areas.

Millions of jobs depend on our trade with the EU.

Tony Blair likes to cite the figure of three million British jobs at stake. Funnily enough, this was precisely the figure quoted by Edward Heath during the 1975 referendum campaign. As it turned out, almost exactly three million jobs were lost during the 1970s immediately following our accession, although others were found elsewhere. But none of this is here or there. For the conflation of EU membership with access to European markets is a false one. Plenty of countries, not just the EFTA members, enjoy free trade with the EU from outside: Greenland, the Channel Islands, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey and others. The easy way to answer the Prime Minister is to point to the fact that every member of EFTA exports more per head to the EU than does Britain. Let me repeat that: EVERY MEMBER OF EFTA EXPORTS MORE PER HEAD TO THE EU THAN DOES BRITAIN. Indeed, both Norway and Switzerland sell more than twice as much per capita to the EU from outside as Britain does from inside. Of course their businesses must meet EU standards when selling to the EU — as exporters the world over must do. But they are spared the cost of applying these standards to their own territory. In fact, almost the only job that would definitively disappear if Britain left the EU is — ulp! — mine.

Britain is nothing like the EFTA countries: they are small and rich.

Yes, they are. But this is surely to beg the question. For as long as I can remember, we have been told that Britain must join the EU because we are “too small to survive on our own”. Now, without a blush, Euro-enthusiasts have turned that argument on its head. All of a sudden, we are too big to do as well as the EFTA tiddlers. Alternatively, we are asked to believe that these countries owe their wealth to vast natural resources. But this argument simply does not stand up. True, Iceland has fish — and so would we, but for the ecological calamity of the Common Fisheries Policy. True, Norway has oil — and we are the only net exporter of oil in the EU, which is why we should be so alarmed by the attempt to define energy reserves as a “European common resource”. True, Switzerland has banks — and Britain, in the City of London, has the world’s premier financial centre(although it will not remain that way for long if it continues to be asphyxiated by EU financial regulations). If 7.4 million Swiss, 4.6 million Norwegians, 280,000 Icelanders and 18,000 Liechtensteiners are able, outside the EU, to enjoy the highest standards of living in Europe, how much more could 60 million Britons achieve?

Outside the EU we would have no influence in the world.

At the risk of stating the obvious, a country is generally more influential if it has a foreign policy in the first place. Norway, for example, has one of the most active diplomatic services in the world. Its representatives are playing a leading role in, among other places, the Middle East, Sri Lanka, Sudan and South East Asia. Being outside the EU’s cumbersome development programmes, it is able to use overseas aid as an instrument of foreign policy. Norwegians are regarded as reliable, neutral arbitrators of third country disputes. How much of this, one wonders, would be true if they were one of the EU’s smaller members? As one of their ambassadors explained:

“Our worst time was just before the 1994 referendum [on EU membership]. Since everyone assumed that we were going to join, I was always being asked to meetings with my 15 European counterparts. Often, I wouldn’t even get to speak. Once we voted ‘no’, people had to start dealing with me separately again.”

The Swiss, although deeply suspicious of international entanglements, none the less manage to host most of the big international organisations, including the Red Cross, the IOC, FIFA and large chunks of the UN. Iceland, with a population about the size of Croydon’s, has received state visits from four US Presidents, two Russian leaders and, most recently, the Chinese premier, who stayed for several days to study the island’s economic success. The EFTA countries have evidently judged that they have more influence by conducting their own international relations than they would have as tiny statelets within the EU. Surely Britain, with its immense global experience, the fourth largest economy in the world and the fourth military power, would be able to retain a global presence without having to go through Brussels.

Outside the EU, we would have less influence in Europe.

This is undeniably true. We would have little say over interest rates in Belgium, agricultural policy in Slovakia or youth training in Finland. Conversely, of course, we would be free to determine our own policies in areas which are currently subject to the EU. Every country would therefore be freer to adopt whatever approach suited it — which strikes me as a pretty good deal.

To pull your weight in trade talks, you have to be part of a big bloc.

The EU certainly has a powerful voice within WTO negations. But the assertion that Britain maximises its influence by pooling its commercial policy with others is true only insofar as British interests resemble those of its fellow EU members. To the extent that Britain diverges from the mean, it will suffer. In practise, Britain has a very different economic profile to most Continental states. In particular, it conducts far more of its trade with non-EU countries than does any other member, and so has a commensurately strong interest in global liberalisation. Yet it often finds itself lending weight to a common European position that is directly inimical to its own interests. The most spectacular example is agriculture. British farms tend to be larger and more efficient than those on the Continent, and Britain — unusually in the EU — is a net importer of food. Our farmers and consumers therefore stand to gain from free trade in farm products but, under the terms of the Common Commercial Policy, we are forced to argue against that goal for the sake of protectionist interests in France, Italy, Bavaria and elsewhere. The same is true of textiles, coal, steel and road vehicles — all areas where the EU maintains high tariffs, which disadvantage Britain, for the sake of Continental producers. Quite how badly Britain is served by the EU’s trade policy is illustrated by the following extraordinary fact. The EU has negotiated preferential trading relations with all but ten of the one hundred and ninety WTO members. These ten states are Australia, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and the United States. Can it be a coincidence that six of these ten territories should be Anglosphere nations where the absence of comprehensive free trade agreements harms Britain disproportionately? As members of EFTA, we could resume the immensely profitable commerce that we used to enjoy with US and Commonwealth markets — markets, by the way, that have since grown far more impressively than has the EU.

If the EU is so bad, why do the EFTA countries keep applying to join it?

Politicians and diplomats are always keener on supra-national organisations than are the people they notionally represent. But the final decision on EU membership rests with the citizens of EFTA — and they have wisely and repeatedly chosen to vote “No”. The referendums in EFTA countries are invariably accompanied by vague but dire threats of economic collapse if EU membership is rejected. In the event, the EFTA states have handsomely outperformed the EU on almost every measure since 1992.

The EU would never offer us the same terms that it has given the EFTA states.

Why not? Britain is, in fact, in a far stronger position than the EFTA countries. For one thing, we are existing members, starting from a position of being wholly within the acquis communautaire. Instead of having to negotiate from outside to join the things we liked, we would be in the happy position of withdrawing from the things we didn’t like. We have a much larger economy than the EFTA states, and a commensurate voice in the councils of the world. Simply put, we matter more to the rest of the EU. On the day we left, we would become overwhelmingly the EU’s biggest export market. Indeed, in purely commercial terms, we would have a far better hand to play than the EU. For, although we are forever being told that half of our trade is with the EU, the balance of that trade is almost never mentioned. In the years since Britain joined in 1973, we have been in surplus with every continent in the world except Europe. Over the past 32 years, we have run an average trade deficit with the other member states of £30 million per day. It is not normal, in any commercial transaction, for the salesman to have the upper hand over the customer.

At this stage, my pro-EU friends sometimes deploy a rather surprising argument. “It’s not just to do with a rational calculation of economic advantage,” they say. “If we left, the others would resent us. They would never give us favourable terms”. I don’t believe this. The EU states are, for the most part, long-standing friends and allies of the United Kingdom. Their interest in the negotiations would be the same as ours: to maximise jobs and prosperity through free commerce. In any case, even if they wanted to punish us, protectionism is now almost impossible under the WTO rules. But, as I say, I don’t think they would want to. Properly handled, the separation would be amicable. Britain would remove itself from the EU institutions and, in so doing, take with it the constant carping and vetoing that has often characterised its membership. Instead, we would stand alongside the EU as a friend and sponsor — the role always envisaged for us by Winston Churchill. The EU would lose a bad tenant, and gain a good neighbour.

It may be, of course, that I am wrong. It may be that my Euro-phile friends are correct in thinking that the others would be so vindictive that they would impoverish themselves in order to harm us, cutting off their noses to spite their faces. If so, though, what on Earth are we doing with them in the first place?

Appendix

The EFTA network: across Europe and beyond

Countries and entities with which EFTA has concluded an FTA:

Countries and regional groupings with which EFTA has bilateral FTAs:

European Union1

Faeroe Islands

Countries and regional groupings with which EFTA has ongoing free trade negotiations:

Canada

Egypt

Thailand

Countries and regional groupings with which EFTA has signed a Declaration on Co-operation:

Albania

GCC3

Serbia and Montenegro

Algeria

MERCOSUR4

Ukraine

Iceland and Norway have bilateral free trade agreements with the EU in addition to their membership in the EEA. Switzerland’s economic relations with the EU are regulated by a Free Trade Agreement of 1972 and seven bilateral agreements which entered into force on 1 June 2002. A second set of bilateral agreements has recently been concluded. Due to its Customs union with Switzerland, Liechtenstein is covered by the seven Swiss-EU Bilateral Agreements, in addition to its membership in the EEA.

The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) comprises Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland.

The Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) comprises Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) comprises Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay.