Conference: Integration marching on

Ignoring the French Non and the Dutch Nee the EU takes more powers

Christopher Booker

Dr Ruth Lea CBE

Professor Ken Minogue

Speech by John Midgley

Mr Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen:

On 21st October 1805, 20 miles south of Cadiz and 12 miles south-west of the shoaling Cape Trafalgar, at approximately midday, a famous conflict commenced.

A British fleet under the command of Admiral Lord Nelson, himself aboard H.M.S. Victory, sailed into battle with a combined French and Spanish fleet.

By 5pm that day, 18 of the 33 strong, combined fleet, had surrendered to the British, in one of the best naval strategies in history.

On the 28th June 2005, a matter of yards off the coast of Portsmouth another conflict took place. This time between a "Red fleet and a Blue fleet". It was billed as a re-enactment of an "early 19th-century sea battle".

The Sunday Times (22 May 2005) reported that organisers of the event, to mark the bicentenary of that great battle at Trafalgar, had decided to tone down the event for fear of causing offence to visiting dignitaries, particularly the French, who would be embarrassed at seeing their side routed.

Admiral Nelson was sunk, by a wave of political correctness.

Political correctness is extremely complex, widespread and rife. And, in my opinion, there is nothing correct about it.

It encourages offence to be taken where none is intended and is a serious threat to free speech.

Those who peddle political correctness are very clever but their tactics amount to nothing more than bullying.

They brand anyone who stands up and disagrees with them as an "ist" or "ic" - like racist and sexist or homophobic and xenophobic and so on.

If someone says or does something that is not deemed to be acceptable in politically correct terms they are vilified and left to hang out to dry.

Just remember what happened last year to the Italian nominee for a Commission post, Rocco Butiglione, for reportedly venturing an opinion on homosexuality based on his Christian faith.

This is a travesty of our way of life, for we ought to want healthy debate and freedom of expression in a free society. Those who espouse political correctness may preach the virtues of tolerance, but are decidedly intolerant when it comes to those who do not share their vision.

We all know examples of political correctness - from changing the names of words containing "man" or "black" to the institutionalised political correctness that pours out of government of all levels on a daily basis.

We can't blame the EU for all of this.

We haven't yet got as far as the European Union Directive in nursery rhymes where our Brussels masters seek to ban "Polly Put The Kettle On" for its contribution to sexism; "Baa baa black sheep" for stoking up racism; "Three Blind Mice" for offending the visually impaired; or "Humpty Dumpty" for having the temerity to fall off a wall and thereby contribute to the compensation culture!

No. It is far more serious than that. The EU is institutionalised political correctness writ large.

I shall try to highlight a few areas of concern this morning - including the European Union's interference in the field of race relations, its grant giving powers, and the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Or, as I prefer to call it - the Charter of Fundamental Wrongs!

Back in 1997, the European Union established a Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia. Notwithstanding that this is an issue which should be determined at nation state level, it has interfered with and contributed to the changes in our national law on race discrimination.

Changing the burden of proof in race discrimination cases from employee to employer - which is not just a legal hurdle but a costly economic hurdle for many of our small firms.

Building up its databases on discrimination in housing and education - giving it more scope to interfere in areas which should only be of national, local or even personal concern.

Notwithstanding its existing budget of £5.5 million, it continually seeks to expand its empire.

Having fingers in all sorts of pies - from the issue of so-called "race crimes" to reporting on the July bombings here in London.

Its stated vision for the EU is a "multicultural" one. In an organization containing many States and nationalities, this may at first seem to be not too controversial an aim.

Yet, how does this translate down to the implementation of policy at a national level?

Are we not debating now - more so after 7th July - the fact that multiculturalism is not working? Britain is self evidently multi-racial. Yet the difficulty with the concept of multiculturalism in the way that it has been pushed is that it can loosen the bonds that tie the British nation together. Our shared history; an intrinsic belief in freedom and democracy; and, equality under the rule of law - not one law for one group of people and another for the rest.

Not satisfied with its existing workload, there are plans to expand this European quango's remit into a Fundamental Rights Agency - policing the Charter on Fundamental Rights and spreading political correctness into Eastern Europe.

The Sovietisation of the European Union!

If he were alive today, I wonder what Ronald Reagan would be calling the "Evil Empire."

The politically correct tentacles of the European octopus stretch further into our national life through the subsidy culture that it operates. I will highlight but two today.

First, the European Social Fund has helped to fund a number of PC projects including the 1990 Trust which runs the Black Information Link, a website aimed at the black community.

If you give money to one section of the community, you have to question what this does to foster a sense of community spirit and community cohesion.

You also have even more cause to question the value of such funding when this group is politically motivated - for example:

- On 10 November 2003, it challenged Shadow Home Secretary David Davis to prove that "he is no longer soft on racism".

- On 17 February 2005, it condemned Conservative Party plans to introduce health checks for immigrants as "racist".

- On 21 February 2005, it suggested that there should be a black caucus and an all-black shortlist after the West Ham Constituency Labour Party failed to select a black candidate to succeed Tony Banks MP.

- Yet, on 22 February 2005, however, it unashamedly urged its readers to lobby the Standards Board for England in support of Ken Livingstone following his verbal attack on a Jewish Evening Standard journalist.

Second, only 2 weeks ago there was a 4 day conference with 141 participants from 41 countries funded by EU taxpayers money.

The European Youth in Action for Diversity & Tolerance declared amongst other things:

- It's not sufficient any more to believe in tolerance (so, does that mean we want a healthy dose of "intolerance" thrown in?

- We should encourage affirmative action to avoid tokenism (but isn't positive discrimination patronizing and tokenistic?)

- We should encourage critical thinking through education (unless of course you take a different view to us!)

Yet the best part of their worthy declaration had to be this gem of political-speak:

"We as participants of this conference, struggle to raise political awareness on this declaration and to ensure its implementation on a national level. We identify ourselves as multipliers, commit ourselves to be multipliers, and by doing this, we will empower youth."

You know they could have phrased it oh so differently. The translation would have been much easier. To paraphrase a former Liberal leader: "Go back to your country and prepare for political correctness!"

Yet this is only the tip of the iceberg. The European Constitution and the Charter of Fundamental Rights will institutionalize political correctness to a much greater degree.

Although the French and Dutch people have voted against the Constitution, we should not be surprised if the European political elites work night and day to introduce the Charter.

History shows that they treat unfavourable referenda results as little more than an inconvenient delay.

The Commission has said that it will implement it across all EU legislation without waiting for it to come into force. It will seek to deliver the Charter as though it was an embarrassing guest being sneaked in via the tradesman's entrance.

The Charter is a ticking time-bomb of political correctness waiting to explode in the UK. Far from having the legal status of "the Beano" as former Europe Minister, Keith Vaz, once said, it will be granted full legal force.

We do not even need to wait for European Court of Justice judges to interpret the law in their usual touchy-feely and highly regulatory way. It is as plain as a pikestaff that the Charter represents institutionalised political correctness.

Just take the preamble which, so far as European judges are concerned, is the meaty bit in the law and the starting point for their interpretation of the other articles within the Charter:

"Conscious of its spiritual and moral heritage, the Union is founded on the indivisible, universal values of human dignity, freedom, equality and solidarity..."

But no doubt - not the dignity to be a citizen of your own nation state; the freedom to make your own laws; the equality of opportunity & not the equality of outcome so beloved of those who hold the banner of collective solidarity above the flag of individual liberty.

The preamble continues:

"The Union contributes to the preservation and to the development of these common values while respecting the diversity of cultures and traditions of the peoples of Europe as well as the national identities of the member states...."

The imposition of the human rights doctrine in British law does not sit well alongside our common law tradition - so how can it "respect" our national identity - our British way of doing things? This will have an impact on very important matters like the way our courts interpret our laws.

Time and again, the European Court of Human Rights and the Human Rights Act (1998) have conflicted with other statute laws and they are a recipe for politically correct chaos.

The Charter will compound these problems especially as it states that it "reaffirms" amongst other issues the case law emanating from both the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights.

The Charter and the Constitution would fetter the discretion of national Parliaments still further, extend political correctness and undermine common sense.

Even if you look beyond the preamble to specific Articles within the Charter - some which eerily mirror the European Convention of Human Rights - you will find a not so favourable tapestry of political correctness being woven. Taking at random, a few examples:

- Article 1: Human dignity is inviolable. It must be respected and protected.

- Article 12.2: Freedom of assembly and of association. Political parties at Union level contribute to expressing the political will of the citizens of the Union.

- Article 21.2: Any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibited.

- Article 22: The Union shall respect cultural, religious and linguistic diversity.

- Article 23: which talks about equality between men and women in all areas but adds

"the principle of equality shall not prevent the adoption of measures providing for specific advantages in favour of the under-represented sex" - in other words "positive discrimination."

It doesn't take a genius to predict that our courts are going to be log-jammed with cases based on the Charter. For example, I can easily see how the travelers' cases - often supported with taxpayers' money through the Commission for Racial Equality - could rely on at least 2, if not 3, of the above Articles.

Political correctness is often about a small group of people trying to foist their views on a majority, relying on the silence and decency of the majority to allow even the most bizarre of ideas to become the norm.

Given this, is it not worrying that the Charter states that political parties should express the will of the people of the Union? How is the will of the people to be defined? What would happen if the will of the people was that they were in favour of free market economics or that they wanted to end or curtail Britain's involvement with the European Union? The Charter would not allow this, given its commitment to red tape, equal rights and socialist economics as well as its clear determination for political union not political separation.

One can only assume that the will of the people really means the will of the constitutional draftsmen, bureaucrats and European Court judges who will implement or develop case law based on it.

The spirit of the Charter not only lives and breathes through the activities of the EU but is also likely to find its way into British law through the Government's proposed new vehicle for institutionalised political correctness (the Equalities and Human Rights Commission) with estimates putting the annual cost for this body at around £70 million.

This is the way to a more controlling State at European & national level.

Just last week we were remembering those who paid the ultimate price for freedom.

They didn't fight for freedom only for it to be shattered decades later.

Yet political correctness undermines freedom, our British way of life and breeds intolerance and resentment which will make Britain a much less stable and happy place to be in the future.

The EU will only make this situation worse. It will increase political correctness through laws, directives, charters, the funding of PC bodies and any other way it can think of.

So we need to guard against every single one of these attacks on our liberty and defend this country from this modern day invasion.

We've won before. And we can - and we must - win again.

Speech by Christopher Booker

Let me start with two little specific instances. I don't know whether any of you were sad enough to listen the other day to the two contenders for the Tory leadership being interviewed on Women's Hour. But the presenter began by giving them each a minute to explain how they proposed to win what was condescendingly described as 'the women's vote'. David Davis began by saying that until the mid-1990s the Tories used to get majority support from the women of Britain, and they first had to acknowledge why this was no longer so. The chief reason, he said, was that the Tories had become too obsessive in talking about issues which were of interest to politicians but not to ordinary people, such as 'Europe'.

This was interesting because, if one thinks of the explanations generally given for why between 1992 and 1997 the Tories lost 5 million votes, high on the list is the devastating blow given to the Tories' reputation for competence by 'Black Wednesday' and the recession associated with our two years in the ERM. Since that time the Tories, having in 1992 won the largest popular vote in history, have never been ahead in the polls again. So a very significant factor in the collapse in Tory support was the Exchange Rate Mechanism, which we only went into because of the way our political leaders were hypnotised by 'Europe'. Yet David Davis suggests that this is an issue only of interest to politicians, which shouldn't be talked about in front of ordinary people or women.

Mr David Cameron, on the other hand, has said more than once that we should take back one or two powers from the European Union, such the right to make our own social and employment policy under the Social Chapter. When asked how he proposes to do this, he likens it to Mrs Thatcher demanding a rebate on our contributions to the Brussels budget in the early 1980s. One has to wonder whether Mr Cameron has the slightest idea how the European Union actually works. For Britain to be given back any powers from Brussels would require a treaty change, and this would require the unanimous agreement of all the other 24 members. Any one of them could veto it. Yet the situation when Mrs Thatcher was battling for her rebate was completely the reverse. The rebate was negotiated as part of an agreement on the EU budget, which also required unanimity. Thus on that occasion it was Mrs Thatcher who held the veto in her hand, able to block the budget unless she got what she wanted, which was why all the others were forced in the end to give way to her.

I start with these two tiny examples because they illustrate a larger and more general point. So blinkered and distorted in this country is the understanding of what is loosely called 'Europe', that our politicians usually go to almost any lengths to avoid talking about it. And when they do, they usually betray such a childlike ignorance of it that it would have been better if they'd kept their mouths shut anyway.

Why, after all, is this 'Europe' so important to us? Simply because it is a system of government. It is in very important respects the government of this country; the peculiar form of government which has come to play an increasingly central role in deciding the policies by which Britain is run and in passing the laws which rule our lives. Yet so firmly is this stuffed away out of sight that most of our elected politicians not only try to ignore it. They are astonishingly ignorant about it. Ask a few questions of the average politician - or indeed of the average newspaper editor or political journalist - and you will find that the vast majority of them no longer have a working knowledge of how our country is governed or how our laws are made. This cannot have been true at any time in history before.

This was one of the reasons why, a few years ago, my colleague Richard North and I decided that we would write a history of the European Union. Not because we knew more about than anyone else, but because we had learned enough, in ten years of studying how it worked in practice, to recognise just how little we or anyone else seemed to know about how this extraordinary project had come about, when and why it had started, what was its true nature and where, therefore, it might be heading for.

When we embarked on our researches, what we were not prepared for was to discover just how much all the previous attempts to tell this story had got it wrong. We looked at all the established histories, and it was not long before we began to see how literally every part of the story had either been hopelessly misunderstood and misrepresented, or had just remained hidden away in the archives.

One of the most fascinating things we were able to unearth - I remember talking about this last time I stood on this platform - was the true story of how the whole project had originated in the first place. A very good test of anyone who claims to know about what today we call the European Union is to ask them why it is structured in the way it is, round four central institutions - the European Commission, the Council of Ministers, the European Parliament and the European Court of Justice. You won't find this explained in any of the standard text books, but the answer is quite simple. It is because the original blueprint for what they called the 'United States of Europe' was devised in the 1920s by a Frenchman and an Englishman who worked at the top of the old League of Nations, which was structured round those same four institutions: a Secretariat, a Council of Ministers, a parliamentary assembly and a Court of Justice. It was precisely this model which was eventually to be used to set the European project on its way.

The Frenchman, who far more than anyone else was to be responsible for translating this original dream into reality, was of course Jean Monnet, who back in 1920 had become the first deputy head of the League of Nations at the age of only 31. It was he and his English friend Arthur Salter who became possessed by the central idea that, to create their United States of Europe, they needed to set up a body which was 'supranational', which was designed gradually to take over the powers of national governments. It was Monnet who conceived the idea that this gradual takeover should be achieved by working one step at a time, beginning with the European Coal and Steel Community, which was entirely his own creation. And it was Monnet who agreed with his other friend Paul-Henri Spaak that, although their real goal was to create a politically united Europe under a single supranational government, the only way they were going to achieve this was by concealing its true aim. They must pretend that it was intended just to be a matter of economics, trade and jobs. An economic community. A Common Market, as was brought into being by the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

There was only one other man who was eventually to have as much influence as these three on how the project would eventually near its goal, and that was the ex-Communist Altiero Spinelli, who, in 1941 in a Fascist prison, sketched out his manifesto for how a federal United States of Europe should be created after the war. Like Monnet and Spaak, he foresaw that it could not possibly be achieved all at once, but would have to be quietly assembled piece by piece, without letting on to its true purpose - until finally enough of the new federal system was in place to call a convention to draw up a constitution. Only then could the peoples of Europe be consulted, when they would be asked to endorse it by acclamation as just what they had wanted all along. And as I am sure many of know, it was Spinelli who, in the last seven years of his life, did more than anyone else to lay the foundations for the next two treaties which were to turn the European Community into the European Union, the Single European Act and the Treaty of Maastricht. It was only appropriate that in 2002, when delegates assembled in the largest complex of office buildings in Europe, the Brussels headquarters of the European Parliament, to draft a Constitution for Europe, the largest of those buildings should have been named after Spinelli.

All this and much much more was faithfully chronicled in the book which Richard and I published in 2003, The Great Deception, subtitled The Secret History of the European Union. But this week we have published a new and heavily revised edition of that book, to take account of all that has happened in the past two years: above all the final agreement and then the virtual collapse of that famous constitution. And, to mark the way our book has changed, we have now given it a new subtitle, Can the European Union Survive?

As events and our own understanding of them have moved on, our new book includes a number of significant new ingredients. One is a rather clearer understanding of what has been perhaps the cleverest of all the strategies which have been used to bring the European project to its present stage of development. That is the way it has never attempted to replace the existing structures of Europe's national governments, but has gradually taken over their powers from behind the scenes. The familiar landscape of national governments, parliaments, monarchies, judicial systems has all been left in place. But they have been subtly hollowed out from within, so that as their powers have gradually been transferred to the new system of government above them, most people have remained blissfully unaware of what has happened.

Much more obvious, of course, has been all the drama surrounding the constitution itself, that extraordinary ramshackle document which was intended to be the final unveiling of what the project was all about, the attempt to create a single, central, supranational government for all the 450 million citizens of Europe, with more to come. This was to be the moment when, as Spinelli prophesied from his island prison 64 years ago, the citizens would finally recognise what had been done in their name and would vote it into being, as marking the culmination of 50 years of work, the final triumph of the project.

Well. Oh dear. As we know, it hasn't turned out like that; and there is no getting away from the fact that the collapse of the constitution has marked a quite unprecedented setback. In fact it has been the most serious reverse inflicted on the dream of Monnet and Co since he so brilliantly put his Coal and Steel Community into place 50 years ago, telling its members as they assembled that they were 'the first government of Europe'.

But stand back and, as I am sure many people in this room are aware - indeed as is usual with this project - we see that not all is as it seems. As some of us have been tirelessly trying to point out - very much including Daniel here, and my good friends Richard and Helen Szamuely on their brilliant daily blog - one of the most bizarre features of recent months has been the way those behind the project have kept it rolling on, just as though the rejection of the constitution by the voters of France and the Netherlands had never happened.

It should only have been when the Constitution was ratified, for instance, that the Charter of Fundamental Rights would come into force. It was only the Constitution that would authorise the EU to draw up its space programme and to set up a European Defence Agency to co-ordinate the integration of the EU's defence efforts. Yet there in Vienna we see it already setting up the European Human Rights Agency to enforce the Charter of Fundamental Rights. There in Luxembourg next month we shall the European Space Council getting on with the drawing up of a European space programme. And there in Brussels, since last January, we have seen the European Defence Agency, under a senior British civil servant, already hard at work co-ordinating the integration of the EU's defence efforts.

There are innumerable ways in which the project is still roaring ahead quite regardless of what the peoples of Europe may think about that constitution, and perhaps none of these are more significant, certainly for Britain, than the stealthy way in which those who rule us are proceeding almost headlong in their rush to integrate our defence forces and their equipment with those of our continental partners. Anyone who has been following what Richard North has been up to in recent months, as reflected in my column in the Sunday Telegraph, will be familiar with some of the details of this remarkable new phase in Britain's integration with the EU. And when I speak about how this is being done by those who rule us, don't get me wrong. As so often, this is not something being done to Britain by people over there on the Continent. A leading role in this latest process of integration has been played by British civil servants, with our politicians tagging along in their wake, and there are two things above all which are alarming about it. One is the way it is threatening an end to the 60 years of our special relationship with America, not least by the way it is drawing us into a growing alliance with America's greatest potential enemy, Communist China. The other is the lengths to which our government seems prepared to go to conceal and to deny what is happening.

There are many reasons, I fear, for very considerable gloom about where our entanglement with this European project is leading us, and about where the EU itself is heading. For 50 years, without ever revealing openly what they are up to, its promoters have been gradually piecing together a system of government like nothing the world has seen before, until today, more than ever, we can see how, in its almost boundless ambition, it has overreached itself. Wherever we look at its operations in practice, from the euro to enlargement, from the single market to the environment, from its common foreign policy to its common defence policy, from fisheries to agriculture, we see that it simply isn't working. All the contradictions implicit in that massive act of deception and self-deception are beginning to close in on each other.

It is no good protesting that the European Union is not democratic, because it was never intended to be. It was always intended to be a government of wise and powerful technocrats, men like Jean Monnet and Arthur Salter: a government which cannot be called to account or dismissed from office; a perpetual one-party state.

We see our nation today increasingly shackled to an archaically clumsy political and economic system which is desperately failing, at a time when the rest of the world, including China and India, is moving rapidly on into a very different and uncertain future. And what is most depressing of all is the way our political leaders seem completely hypnotised by this process, without really beginning to understand it; so shrunken by it that we watch their playacting, we listen to their vapid evasions and their wishful thinking about how it can all be reformed, with a sense of desperate weariness. They know nothing about it, and what is worse they don't even want to know about it.

It is always appropriate at meetings of the Bruges Group to quote from the politician whose remarkable speech inspired its foundation. I shall end therefore with two sentences from Lady Thatcher's book Statecraft, which Richard and I quote as the heading to the Epilogue of our new book:

'That such an unnecessary and irrational project as building a European superstate was ever embarked on will seem in future years to be perhaps the greatest folly of the modern era. And that Britain, with traditional strengths and global destiny, should ever have become part of it will appear a political error of the first magnitude'.

We should go forth from this hall today meditating on that lesson that she herself so painfully learned. And we should resolve to act on it.

Speech by Ruth Lea

1. Introduction

Discuss:

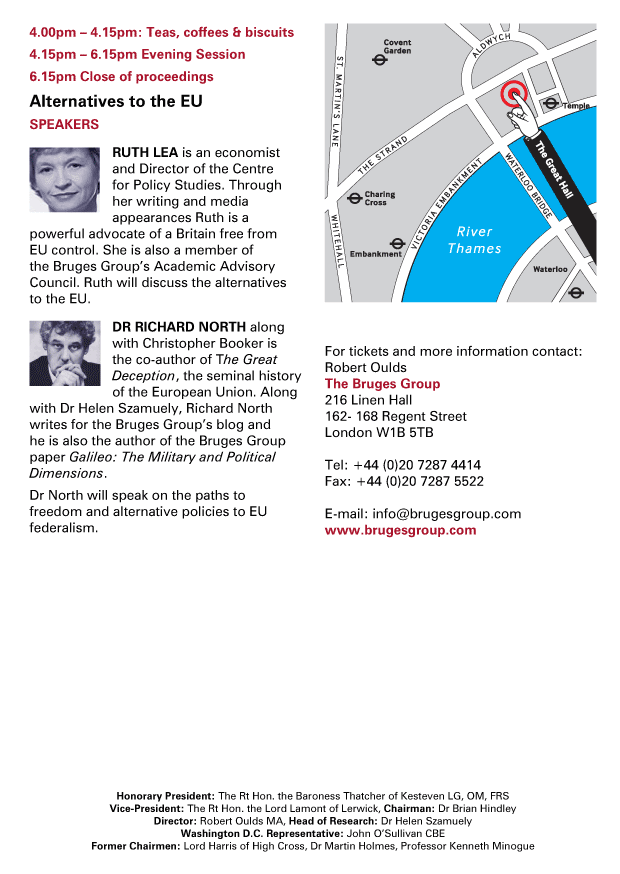

The costs of EU membership

A la carte Europe

2. Initial thoughts on the costs of EU membership

A story that recently caught my eye concerned the European Court of Auditors's latest refusal to approve the EU's accounts. In the words of the Court they refused, for the eleventh successive year, because "the vast majority of the payment budget was again materially affected by errors of legality and regularity". In other words the accounts were riddled with fraud and errors. Yet, so accustomed have we become to the Commission's persistently fraudulent behaviour, the reaction was little more than a resigned shrug. This vignette typifies much of the British attitude to the EU. We don't really like or approve what the EU does but there is a feeling that we cannot do much about it or, more radically, that we could not prosper outside the EU's fraudulent bureaucracy.

And it is costly. The UK is the second largest net contributor to the EU's €100bn (£70bn) budget after Germany. Last year we paid £41/2bn more into the EU's coffers than we received, even after the rebate ("abatement") which was agreed under the 1984 Fontainebleau Agreement to provide the UK with a more equitable budgetary settlement. The rebate is currently worth about £3 to 31/2bn annually but as the tortured negotiations for the EU's budget for 2007-2013 proceed, it is clear it is under threat. Britain's financial contribution to the EU looks almost certain to increase.

Britain is, of course, a rich country and should be generous in funding worthwhile international projects. Humanitarian aid for the world's poorest has huge moral persuasiveness. But funding for the EU, with still half the budget going on the wholly indefensible Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and administered by a Commission condemned by its auditors, seems to be, in economist's understated parlance, a "misallocation of resources". EU financial help for France's riot-torn cities simply looks bizarre.

3. Economic necessity arguments for EU membership: but the costs outweigh the benefits

Of course one can argue that £41/2bn is a small part of Britain's GDP - a mere 0.4% of GDP- and this is but a small price to pay for the benefits, especially the economic benefits, of EU membership. After all, the argument for British membership of the EU was always overwhelmingly in terms of economic prosperity. But this begs the question about just what the benefits are and, moreover, there is mounting evidence that any benefits are significantly outweighed by the costs.

The people who still believe that EU membership is the right thing for this country argue the case in economic terms; that EU membership is an economic necessity. We who believe that the EU membership is unhelpful for Britain must argue that EU membership is not in Britain's economic interests. This, ironically, is the political case that we must make. The question we must all be prepared to answer is "is EU membership in Britain's economic interests?" Yes or no. And we must think how to sell this to the people of this country. Let's talk economics.

The people who argue on the economic grounds must tell us what the economic benefits are. And yes there is mounting evidence that any benefits are significantly outweighed by the costs.

- For example, the aforementioned CAP, protectionist and discriminatory, remains one of the major sticking points to a further opening up of the world markets, which could greatly assist developing countries. CAP could yet scupper the WTO's current Doha Round of trade talks.

- Our membership of the EU's Customs Union means we are unilaterally incapable of negotiating any trade deals. This was poignantly demonstrated in the recent "bra wars" skirmish, in which Trade Commissioner Peter Mandelson capitulated to the protectionist pressures from France, Italy and Spain - to our cost.

- And the potential benefits of the Single Market are compromised by a Commission mindset that fears free markets and favours costly regulatory compliance and control. The Financial Services Action Plan, for example, is a monster with very high compliance costs for the financial services industry.

Moreover, the infamous rallying cry that "3 million jobs are dependent on trade with the EU" looks less than persuasive when we note that Britain appears to have a structural trading deficit with the EU. Last year the current account deficit with the EU was £22bn, of which £12bn was with Germany. If 3 million jobs depended on exports to the EU, then 3.3 million jobs were lost because of imports from the EU. The other EU countries have a very good trading deal with us, which they won't want to damage.

And then there is the work of Patrick Minford and Ian Milne who, when you take into account all the costs (CAP, trade diversion, regulations etc) EU membership could be costing the UK a staggering 25% of GDP.

4/a Time for a change: à la carte Europe

So Budgetary costs apart, the evidence is stacking up that, far from aiding our prosperity, membership of the EU is positively harming it. It is time to shed the CAP, regain the ability to negotiate our own trade deals and reject the Commission's strangulating red tape. Of course, this would mean a major redefinition of our relationship with the EU. But, given the tectonic shifts in the global economy, the time is ripe for discussion of alternatives. I have already promoted the notion of an "à la carte Europe", in which countries individually choose the nature of their relationship with the EU, as the modern model for European countries.

There are real tensions developing in the EU, which are likely to get worse rather than better. These tensions argue strongly for an "à la carte Europe" as a possible resolution. And those tensions relate to:

Firstly, the eurozone.

Secondly, the conflict between, to put it very crudely and simplifying dramatically, two economic models for Europe:

On the one hand, the model characterised by high taxes, heavy regulation and protectionism, which is often referred to as the "Social Market Model" for convenience's sake, favoured by "Old Europe".

On the other hand, the model characterised by lower taxes, lighter regulation free markets, favoured by the UK (maybe) and "New Europe".

4/b A la carte Europe: tensions in the eurozone

There is no doubt that tensions are mounting in the eurozone. All too predictably the "one-size fits-all" interest rate policy is failing to accommodate the needs of the very diverse economies of the eurozone. In the words of the OECD, there is a "chronic pattern of...divergent activity".

Germany's economy is expected to show weak growth for 2005 despite some signs that Germany's competitiveness is improving and growth was better in the 3rd quarter (up 0.6%). But unemployment remains at around 10%. Exports have been doing well, but offset by growing imports, and the domestic economy looks sluggish. There is an awareness that structural reforms are required but, as shown, by this week's election results, the country is in no mood for serious reform.

France's situation is, arguably, less dire (GDP was 0.7% up in Q3) but an unemployment rate of around 10%, by any standards, is a symptom of an economy which is seriously under-performing. Italy's economy, especially vulnerable to cheap imports from China and the high value of the euro, is in recession (despite the 0.3% increase in GDP in Q3). The eurozone's "big three" economies are failing to rise to the challenge of the intensification of global competition, reflecting the rise of China and India, and are continuing to under-perform compared with most of the world's major economies (including the British were growth has been quite modest).

Meanwhile there remains reasonably healthy growth in Spain, Ireland and Greece. These diverse economic fortunes, along with the spectre of increasing inflationary pressures, have prevented the European Central Bank from cutting interest rates. But with weak growth persisting in the major economies, pressures are growing for the ECB to reduce interest rates, not least of all from the OECD.

The ECB cannot, however, rectify the problems of economic divergence, which will surely persist. Diverse economies require diverse policy responses and there is already discussion of extreme scenarios, such as the break-up of the euro, so that the individual economies can go their separate policy ways. One such example was an article in 2005 in Le Figaro which quite explicitly asked the question whether the eurozone would finish by exploding. Suffice to say the journalist avoided a straight answer, but the fact that this issue is even being discussed in the mainstream French press is extraordinary in itself, and would never even have been contemplated in the heady days of the birth of the euro. In Italy there is increasing speculation about the euro's future. And Der Stern, a German magazine, ran a report of a meeting in Germany in 2005 where the euro was discussed, which was attended by economists, some of whom had warned about the possible break-up of the euro.

The euro is not about to break up but stresses are rising. And, in the longer term, it is difficult to envisage the currency surviving unless there is de facto political union of the eurozone states. Historically, all major monetary unions outside political unions have broken up.

4/c A la carte Europe: conflicts between different economic models for Europe

Now onto the conflicts between different economic models for Europe. Firstly, a few words on the high tax, protectionist, heavily regulated and inflexible Social Market Model as defended by "Old Europe", especially France, and which is simply failing to cope with the changing global realities.

There is very little stomach in "Old Europe", France, Italy & Germany, for any market led reforms of the Social Market Model. One of the reasons why France voted against the Constitution was because it was seen as too "Anglo-Saxon", when it explicitly enshrined the European Social Market model. The EU is already too free-market for France's socialist and protectionist tastes. In Germany, Chancellor Schroeder's modest labour market and welfare reforms contributed to his political difficulties. New Chancellor Angela Merkel's relative failure in the polls has killed any prospects of serious reforms in Germany.

The model still has power to exert influence on EU policy making. The Services Directive was watered down by President Chirac partly because it was seen as too Anglo-Saxon and might lead to "social dumping", with the shocking prospect of businesses moving to the more dynamic and competitive EU countries from the less. And during the recent "bra wars", quotas for Chinese clothing imports were imposed mainly at the behest of France, Italy and Spain, which have textiles industries to protect.

The UK has long been a critic of the Social Market Model (though an ambivalent critic in that the current Government is damaging its competitiveness by increasing the regulatory burden and taxes). It has, arguably, gained allies with the accession of the new member states. Although the economies of "New Europe" are small (barely 5% of total EU GDP), their entry as mainly experienced reformers has changed the political dynamics of the economic debate in the EU, ruffling feathers on issues from tax reform to trade liberalization. Moreover, many of the leaders (albeit ex-Communist) of the new countries have close connections with the US, which they see as a liberator and not a threat, and they are imbued with the ideas of free markets and liberty. Angela Merkel, on a personal basis, is very much as case in point. Some people argue that the countries of "New Europe" will eventually embrace the protectionist high tax, heavy regulation Social Market Model as they become absorbed into the EU. I'm not so sure.

Several of countries of new Europe have instituted aggressively competitive tax regimes (Estonia has a 0% corporate income tax rate on retained profits) and are unlikely to wish to saddle themselves with the failing policies of the high tax, protectionist Social Market Model. The attempt to impose screeds of regulation across an expanded Europe of 25 nations simply looks delusional.

Conflicts between the defenders of the protectionist Social Market Model, as immune to "Anglo-Saxon" reforms as ever, and its critics are therefore intensifying and can surely only intensify further. For the time being, the EU will probably continue to "muddle through" - but this is no long-term solution.

4/d A la carte Europe: conclusion

The tectonic plates of the global economy are inexorably shifting and no country can ignore this. The economics are driving this debate. If European countries are to retain prosperity they must be globally competitive. And individual European countries should be free to respond to the "competitiveness challenge" as they believe to be appropriate. The sooner this is acknowledged, the better.

Serious consideration should be given to a restructuring of the EU along "à la carte" membership lines, in which all EU member states should be permitted, if not actively encouraged, to decide whether or not to participate in specific EU institutions and policies. Member states should be permitted to decide on the nature of their membership of the EU. If certain countries, the UK for example, wished to redefine their membership as one of free trade, along with constructive inter-governmental cooperation on other issues, then this "minimalist" package would, in an "à la carte Europe", be accepted as not just feasible but positive as well.

At the same time the "core" eurozone member states could be given free rein to push for a de facto political union, to give the necessary political support for the euro including the necessary fiscal transfers, without being held back by the laggards. If they do not do this, then the currency will surely not survive.

5. Where are we now?

It's time to revisit the idea of an "à la carte" Europe.

After all, a form of "à la carte Europe" already exists with Norway and Switzerland, EFTA members, which are indubitably part of Europe even though they are not signed up members of the EU. This is surely the future for the UK and, doubtless, some other EU member states. The UK should start negotiating for a future which is as unequivocally European as Norway's or Switzerland's but free of the EU's costly, fraudulent and economically damaging bureaucracy. I don't talk about "withdrawal". I don't talk of "getting out". I don't try & ignore the fact that we are part of Europe. I talk about being part of an "à la carte" Europe in which we tell our EU partners that we are freeing ourselves from their cumbersome bureaucracy.

British public opinion has woken up to the cost, bureaucracy & lack of benefit to the British people. Now is the time for analysis on (1) the trading options available (which I'll discuss next) & (2) how we disengage from the EU's stultifying bureaucracy (which I won't discuss here).

6. Models for a free Britain

Let's just look at the 3 basic trading models [options] for a free Britain & its reconfigured relationship with the EU, starting with most integrationist:

- The UK could continue to belong to the EU's Customs Union (CU), with a common external tariff (CET), though no internal tariffs. Peter Mandelson would remain the UK's negotiator within the WTO and with our trading partners. No.

- The UK could form a Free Trade Area (FTA) with the EU, with no common external tariff (CET), no internal tariffs and regain control of its own trade policies vis-à-vis 3rd countries, under WTO rules. But note that a FTA is still discriminatory against non-FTA (non-EU) countries - including the US. There are 2 FTA options:

- The UK could belong to the EU's Single Market, as the 3 "EFTA/EEA" members do (Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein). Note that they are not members of the CAP, CFP, Defence policy, Customs Union, EMU and they pay only a token amount to the EU budget. But they have the costs of complying with the regulations of the Single Market. No.

- The UK could stay outside the EU's Single Market, as "EFTA/non-EEA" Switzerland has done. Note:

- Switzerland has cherry-picked & taken an "à la carte" approach with the EU. AN OPTION

- Mexico, incidentally, has an "arms-length" FTA with the EU.

- The UK could adopt a policy of unilateral free trade where the UK trades completely freely with all countries and does not form a CU or an FTA with the EU (or indeed any other country), under WTO rules. Note, for example, there is no UK-US FTA - even though the strength of the economic relationship between the US and the UK is second to none. Such trade is non-discriminatory and, economically, is the BEST OPTION.

A tentative conclusion is therefore:

- Complete unilateral free trade is arguably the best option.

- But a Swiss-style FTA with the EU, perhaps in conjunction with a multi-country FTA relationship with NAFTA, is a strong contender. These FTAs have the political advantage of providing a political comfort blanket - so we can talk about not being "isolated".

Finally, it is worth noting that two geo-political considerations should intimately inform the UK's choice of global trading arrangements for the next half-century. They are:

- The US will remain the most powerful nation, though China & India growing economically.

- Continental Europe is in long-term economic decline, reflecting economic & social rigidities as well as demographic decline.

We must free ourselves from the costly, fraudulent & economically damaging bureaucracy of the EU and, of course, this would mean the repeal of the 1972 European Communities Act and some hard thinking about how we disengage. We must start thinking now.

Speech by Professor Kenneth Minogue

Freedom and the EU in Today’s Britain

1. I share all the Brugiste criticism of our involvement in the EU, but I also have a wider interest in the cultural tendencies of which the EU is but a part, though a very important part. Hence I hope you will indulge me if I focus my remarks around the question: Why do I feel less free today than I did as an undergraduate in Australia back in the middle of the last century?

2. In those days, I had no rights whereas today I can hardly move I have so many. I had only the one right of the British – to do anything I liked provided I did not break the law. Further, there were restrictive licensing laws (pubs shut at 6pm) and a narrow minded Censorship Board that prohibited the importation into Australia of dirty books such as Ulysses and Moll Flanders – just the kind of up-front idiocy to provide us free thinking kids with a cause, and of course it very quickly changed.

I have no problems of that kind today, and indeed my situation is such that the trammels that affect so many of our fellow citizens don’t affect me. No one has ever actually imposed political correctness on me, for example, and although the state compels me to wear a seat belt and not smoke in lots of places, it happens that these things do not restrict anything that I want to do. So why, you might well inquire, am I into bitching?

3. It is not as if I were affected directly by, for example, the laws that prohibit discrimination between races and religions. I do indeed resent being told how to feel and what to do, but I don’t have any inclination, or indeed cause, to discriminate. Yet this is the point at which irritations do begin to rub. As an academic, discriminating between X and Y is in my blood, and I do in fact prefer some peoples to others. Eg. I am philosemitic, and I rather prefer cheerful Black Caribbeans to some other migrating groups – women in Burkas, for example. In P.C. Terms (as well as in terms of the law on hiring and firing for employers) any preference for one set of people rather than another is the slippery slope to the dreaded “racism”. Yet my response to people is invariably to respond to them as individuals , and I certainly would not be rude or hostile to people whom in general I don’t like. But a miasma of self-censorship in the way one thinks and feels is in these circumstances hard to avoid. It has been institutionalised in the currency of a euphemistic vocabulary, as in “asylum-seeker” for migrant, “Asians” when the issue is actually Muslims, and Travellers when we are talking about gypsies.

Similarly, I feel rather less free because my world is full of people who have learned to parade that they have been “offended” by things that certainly ought not to offend them. When I learn that Barclays and Lloyd’s bank have stopped making “piggy banks” because this is an offensive symbol to Muslims, I feel my world being narrowed by the stupidity of others. The problem in fact is that one demands (as Yossarian in Catch 22 demanded) to know why people wanted to kill me, in this case by planting bombs on the Underground. Similarly I get irritated when a set of rather dumb people set out to engineer my mind. It is rather difficult in our current world to avoid improving messages – even down to the triviality that on every television channel, for example, the sports correspondent is female, so that we may be taught to regard women as being no less interested in and enthusiastic about sport than men.

In the free world in which I grew up, the criterion for getting a position was ability; today the criterion is representativeness of race or religion.

4. You may well be thinking that I have wandered from the point. What has any of this got to do with the EU? Part of the answer, of course, is that the deception, obfuscation, lying, posturing etc. that I am complaining about took a large step forward when being used to reconcile us to the step by step encroachment of the EU on our power to govern ourselves. Abusive terminology was used to suggest that Eurosceptics were nationalists – “little Englanders”. We were charged with being the kind of xenophobes who disliked foreigners.

5. This, no doubt, is pinprick stuff. The more serious point is that committing ourselves increasingly to conform to the laws made in Brussels was part of a wider propensity of twentieth century governments to save the world by signing up to abstract propositions and declarations of rights. And it is here that the basic problem lies. Its technical name is abstract univsersality. It is the technique of subjugating people by the use of high sounding abstractions, and it has two stages:

The first stage is signing up to declarations that make us all feel good, a bit like new years resolutions to be better people.

The second stage, which may happen even a generation or two later is when we discover how circumstances mock us, and how the abstract commitments of yesteryear become the albatross round our necks, of this.

The big question is: Why did we do it? This is a profound question. It can partly be answered by pointing to the artless vanity of statesmen who love parading on the international stage to the flashing of lightbulbs. And at the moment of signing, it all seems so harmless – until you discover, that you no longer control your policy on, for example, migrants coming into the country, or schools unable to regulate the kinds of dress they will permit their pupils to wear, or that governments must neither expel foreigners they regard as dangerous (because the foreigners might be in danger) nor keep them locked up (because judges and rights lawyers have equipped everybody with what used to be the rights of Englishmen.)

Such is the explanation at one level. But I repeat: why do they do it? Why are statesmen so enthusiastic about giving away our control of our own lives?

6. The technical answer to the question of why people sign up to international agreements – and why they are prepared to give up veto powers in the European Union, is “the free rider problem.” If ten countries in the region limit their pollution, but the eleventh does not, then the eleventh gets free ride and continues the damage to the environment. Certain public goods can only be enjoyed if everybody agrees to sign up. It is a version of the social contract theory in Hobbes, where you either join, or become an outlaw.

7. Well yes, up to a point, but I think there is a deeper answer, and it requires that I should explain the problem of what some people call “internationalism” and which I have in other contexts described as “Olympianism.” This is a movement that John Fonte calls “transnational progressivism” – so much a mouthful that others have shortened it to “Tranzis.” The Olympian, or Tranzi, is someone – usually an intellectual of some sort – who believes that nations are just as incapable of making rational decisions as individuals. Individuals and nations share a disabling egocentricity that can only be transcended by international bureaucrats. Just as experts – and the Man in Whitehall – know better than your average citizen what is for the best, so international agreements are superior to the judgements of national governments. They transcend the selfishness of nations, and the good of mankind becomes, for the first time in history, a central consideration in policy. The slogan that “national sovereignty is an anachronism” was the basis on which the EU was constructed, and is also the belief that has led to the creation of international charters and declarations of rights. Wisdom is to be found not in elected governments but in legal and other experts creating rules for the benefit of all. It is this Olympian doctrine that led Jean Monnet, the “father of Europe” always to hate “intergovernmental” agreements. He wanted a mandatory collective judgements.

Olympianism is thus a rather seductive doctrine that promises us the punishment of political crimes, an end to war, “making poverty history, the saving of the environment and other grand benefits. It is a plan aiming to secure the future harmony of the human race. And pretty much the same promise is made by those who espouse the European Union.

The Olympian problem, then, is to persuade the rest of mankind that this Western (or perhaps European) project of judicialising the world is the road to future harmony. Nations are no more keen to give up their powers than are individuals. Wilfulness (on this reading) is the human problem, and the solution is subjecting will to a rule of reason.

In the case of the EU, this pill is sweetened by an interesting promise. The countries that “pool “ their sovereignty (as the process is whimsically put) in order to join the Union are promised that there will be a great access of power to do good because they will no longer be small, feeble national units, but part of a great big Union hundreds of millions strong. And this was certainly what Europhiles, from Edward Heath downwards, promised. But what is the reality of these promises?

a. Europe speaks with one voice on nominations for the UN. The chairmanship of the UN Human Rights Committee comes up. In the whimsical manner by which these things are arranged, it is Africa’s turn to have the chairmanship of the Committee, and the Africans put forward only one name – Libya. And so Britain finds itself supporting this remarkable new move. Would the foreign office have agreed had it been free to advance a better name? I am no fan of the FO, but I suspect it would have.

b. Or consider our present trading problems with China, so hamfistedly managed by our very own Peter Mandelson. It is to our interest to open our markets up to Chinese goods – but we find ourselves hamstrung by the interests of Southern Europeans who seek protection for their textile manufacturers – just as we are hostages to the French on the issue of Third World agriculture. Far from being stronger from our association, we virtually disappear off the map.

c. As Kenneth Clarke disappeared off the map, in suggesting that the EU should espouse a programme of debt relief for the Third World, only to be blocked by Germany. But Britain at least was part of the G7, and could advance its policies for itself in that forum.

8. These are cases where the higher level abstraction - the EU’s collective judgement articulated by the Commission - runs counter to our national inclinations, and our national interest, and also, one might add, it runs counter to many decent moral policies in international affairs. And what we haves hre, and in many other cases, that is a refuting instance of the basic Olympian proposition that international organisations are altruistic while national governments are selfish.

No doubt in some cases of such exchanges, we might gain, but less often, I think, because the negative protectionist tendencies in Europe far outnumber the enterprising ones.

9. One aspect of Olympianism is that, as a form of liberalism, it raises the question of how we ought to understand Great Britain. Again, we are back in the arena of abstract universalism.

Britain is, from one point of view, a historic community going back a thousand years and more, with very definite cultural characteristics – it is Christian, or post-Christian, Anglo-Celtic, devoted to freedom but also sensitive to good causes like abolishing slavery and being charitable to the poor, technologically and artistically inventive and highly individualistic, for example.

Internationalism is not interested in history, except as part of an indictment of our faults before we signed up to international good conduct, and when it does recognises some good features of our past, it seeks to suppress them. Christianity, for example. In Olympians terms, history goes out the window, and we are abstractly understood as belonging to a single humanity with a variety of diverse cultures, which we ought to celebrate as all being (more or less) of equal value. These cultures are divided into regimes as, democracy, dictatorship, multicultural society, etc. The crucial criteria for approving or disapproving of these divisions of the human race include such practices as human rights, standard of living (“poverty”), gender relations, conception of a social past (historically based antipathies must be marginalized and preferably forgotten) level of inequality, and in summary, whether such and such a state may be thought a “good international citizen”, which means signing up for every motherhood ideal presented to it, and acceding to the demands of international organisations. In these terms, Britain is less a historic community than, abstractly, a “liberal democracy” with heavy responsibilities to Europe and to the international community. The basic responsibility is to be a good example to others.

10. Here then are two conceptions of society and politics in Britain.. But they are more than that, being in fact conceptions of reality at war with one another. And they are at war partly because we, or those who commonly speak for us, are keen to advance the abstract conception of Britain as an internationally responsible civil association, and they are correspondingly enthusiastic about denigrating and then giving up the historical conception of who and what we are.

I can now give what I take to be the deepest answer to my question: why do we (as a civil association) sign up to, and then implement, this whole raft of international treaties designed to perfect the world? The answer is that we have all been enrolled, compulsorily, as crusaders for a better world. We have been allocated a role as instruments of a grand cause. That means that we must be keen to support rights and the other improving international conceptions (universal jurisdiction, for example) that are believed to be necessary in defeating poverty, removing civil conflict, protecting the environment and advancing planetary harmony.

Above all, as crusaders for a better world, we must be exemplary. And what that means is that we must exhibit conspicuous international morality. Let me give you some examples:

a. While all sorts of vicious mayhem are going on in Iraq, our troops must be put on trial for infractions that would barely be noticed in the wider context. Hence the soldiers acquitted last week because of ill framed charges based up confessedly lying Iraqi witnesses.

b. Or the indictment of Colonel Jorge Mendonca, which has raised at least a justified suspicion that he has been fingered as part of the abstract principle that officers must be found no less responsible than other ranks. I do not know what the truth of this might be, but many features of our current system (including the conduct of the Crown Prosecution Services) cannot but encourage us to suspect such things.

c. The Home Office in its immigration policies is notably unhelpful to White Zimbabweans in Britain. It has kept their travel documents (D. Tel 14 Nov. 05) for a year, been unhelpful about allowing indefinite leave to return, thus trapping these people in Britain. Now in terms of social policy, these people are not a problem. They are not on welfare, they are not the sort of people liable to rioting, demonstrating or become in any other way the kind of problem that demands a multicultural explanation, yet a system that allows gangsters, fraudsters and people with other social problems in, makes a point of being difficult to them. The numbers are small, and they used in happier days to be described as “kith and kin.” But what the Home Office is now doing is showing how exemplary it is in not preferring Whites to Blacks or Browns.

11. One of the more interesting aspects of this universalisation of the world is religion. In Olympian terms, Christianity is an embarrassment to the West, because although it is historically the source of concepts such as rights, and practices such as experimental science, it is also culturally specific and thus conflicts with the Olympian doctrine that the emerging international world is the product not of any particular culture, but of universal reason itself. This is, in my view, the basic reason why the late unlamented European Constitution firmly avoided any mention of the Christian origins or the Christian character of the European Union. It also accounts for a great deal of the village atheism prevalent in academic circles.

The contrast here is between our indigenous religion of Christianity and the new, and (significantly) highly aggressive religion of Islam, whose Olympian destiny it is to be taken over by the new internationalist imperialism. Muslims, of course, have other and very different ideas about their destiny. The religion of Islam is, from an Olympian point of view, rather unsound on many questions, but above all on that of the rights of women, but the first move in subjecting religions to the new Olympian dispensation is to treat them not as religions but as a rights-bearing bits of culture. Since Muslims blow people up, and stage Intafadas in France and other places, we seem to have a rather intractable problem. The Olympian solution is denial. It is to deny, both by naming and by providing explanations (extremism, poverty, alienation etc.) which suggest that bits of Islam are merely another version of familiar problems of fanaticism and bigotry. The cause of 7/7 underground bombs was dislike of British foreign policy; the cause of the French riots was poverty, and the failure to be accepted into French society. In Britain newspapers and especially the BBC insisted that he bombers were a “tiny minority” of Muslims (if the word was used at all). The better way of putting it was that they were “extremists.” In France, the issue of Islam was suppressed because it might incite Frenchmen to support Le Pen. It was merely a social problem.

12. Here then we have an interesting instance of Olympian explanation being used to describe (or, more accurately to mis-describe) what is going on. A culture in this doctrine is essentially something that can ultimately be assimilated to human rights, and religions as survivals from an earlier and less sophisticated time, may be fitted without serious problems into private observances. This programme leads to a massive distortion of our understanding of what is going on in the world. Earlier this month, three Christian schoolgirls in the Indonesia island of Sulwesi were set upon and beheaded, an item of news worth no more than a brief mention. It took a major anti-Christian riot in Pakistan, apparently provoked by the lies of those who had lost to a Christian at cards, to get any sort of treatment in British broadsheets. Houses, schools, churches and medical centres were burned down by the mob.

13. Abstract universalism is thus not just a feature merely of politics, or of religion, but reaches down into every corner of life – especially in the form of codification. Thus in my own profession of academia, the assumption grows that students are not as bright as they used to be, and that university teachers are perhaps just in it for the easy life, so university teaching becomes codified in the form of “academic audits” by which dons learn how to reach down to the dimmer people, and in the form of the Research Selectivity Exercise, a great paper wasting exercise in governmental control. The particular character of university teaching, so responsive to the individual teacher’s idiosyncracies, must be suppressed in favour of turning professors into instruments of an abstract perfection. Here, as so often in this unreal world of abstract universals, the argument is that we must be brought into line with other countries. We must, for example, imprison the same proportion of our population as they do. And the percentage of our GDP spent on public health should fall into line with theirs. Not much diversity here!

14. It is worth recalling that the national sovereignty that Olympians so despise came into being to solve a problem that Olympians themselves are now replicating. The world of the late middle ages was being constricted by too much law. Societies seeking a way in which to deal with the problem came up with the idea of a sovereign power that could repeal law that was now found constrictive – a brilliant solution, since it kept in being the sense that law was inviolate.

The problem with grandiose declarations of policy is that they cannot easily be repealed. They are often treaty commitments sustained by many complex agreements, so that the national interest can hardly be discerned. Consider for example the marvellous conditions of job security guaranteed by the social charter and by most European governments. These laws have the consequence that it is extraordinary difficult to sack incompetent workers. What to do? According to a recent report (S Tel Nov. 13, 05) the EU has been forced into the expedient of calling in psychiatrists in order to suggest a mental health reason for dealing with someone whom (for good or bad reasons) they no longer want. Those whom the Commission wants to destroy they first call mad, as you might say, echoing the classics.

15. And so I return to the question from which I started: Why do I no longer feel as free as I used to?

My attitudes are being dragooned by social and attitudinal engineering, and authority is no longer content merely to protect me from crime or foreign invasion, but now subjects me to endless advice on smoking, health, sex, parenting, my attitudes to other sets of people, drinking alcohol and many other aspect of my life. Meanwhile the cultural heritage of Britain (and especially its religion) is being subordinated to that of immigrant communities using the weapon of being “offended.” (often this scourge is home grown in bureaucrats working in local councils rather than the actual sensibilities of the immigrants themselves.)

My country is no longer as free as it was to influence the world. It has been submerged in international associations which are corrupt and which muffle the special character of what Britain might directly contribute to the wisdom of the world.

I increasingly seem to be treated as an instrument of (and taxed for) international projects (eg. Overseas development) I cannot influence.

Much of the law that influences my life cannot be repealed, just as the European Commission cannot be un-elected.

I have a life of my own to lead, but the Government construes my life, and that of most of my fellow citizens as valuable only as an instrument to be managed for the benefit of millions of poor people, for whom absurdly, I am told I am responsible.

Authorities, from local councils to the EU and the UN seek to prescribe what I do by taking away my own personal judgement in favour of abstract criteria – a recent case being the proposal that babysitters should face a minimum age qualification. Parliament wants to decide how I should punish my children, and bring us into line with other countries (ie. Sweden). Something called The Commission of Families and the Well Being of Children wants the age of criminal responsibility raised to bring it into line with Europe. Images of Romeo and Juliet have been removed from registry offices lest they “offend” gays. But I need no go on. You all know what it’s like.

Such is the problem. I don’t quite know what the solution is, except to ignore the messages and disobey the petty restrictions. But one might well remember a remark of that acute Frenchman Bertrand de Jouvenal: “A society of cheep will infallibly bring forth a government of wolves.