Bruges Group Blog

The EU Deal Unmasked

By The Rt. Hon. Sir Iain Duncan Smith MP (Conservative Party MP), Martin Howe QC (Intellectual Property and EU Law; Chairman of Lawyers for Britain), Professor David Collins (International Economic Law, University of London), Edgar Miller (Managing Director of Palladian Limited; Economists for Free Trade), and Barnabas Reynolds (Global Head of Financial Institutions, Shearman & Sterling).

In his interview with The Telegraph on October 3rd, 2020, Boris Johnson said that he wants a 'Canada-style relationship' with the EU. A 'Canada plus, plus' agreement was the earlier hope, but the Prime Minister is right to keep it simple for now, thus making it clear he wants at least what the Canadians achieved.

For most of us, that objective seems wholly reasonable as a minimal initial ask. It is in itself a compromise across a range of issues but it has the merit of simplifying the complex negotiating process. Surely if the EU could settle a deal with Canada, then how could it be that such a deal would not be available to the UK, a country that has been a member of the EU for some 40 years? After all, the UK isn't asking for special privileges but only a fair and relatively simple deal, based on a deal already in operation.

Yet, as things currently stand - if indeed a deal is done - the UK's relationship with the EU from 1 January 2021 will be governed by a combination of a 'future relationship agreement' (FRA) and the Withdrawal Agreement (WA) with its Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP) remaining in force, except to the extent that the FRA might modify them. The purpose of this paper is to analyse the impact of an ongoing WA/NIP on the UK's aspirations that the Prime Minister has made clear again and again: that the UK wishes upon leaving the EU to have a Canada style trade deal with our erstwhile partners and ongoing friends in the EU. Specifically, the paper explains

- Why it will be better to have no 'future relationship agreement' at all rather than continuing on the current course of negotiating a 'Canadian minus, minus' deal

- The twelve reasons why the WA (and the associated NIP) - if not fundamentally altered or rejected - make an acceptable Canadian deal impossible

BETTER NO AGREEMENT THAN CANADA MINUS, MINUS

As the following section of this paper makes clear, right now - even as the negotiations are going on - there are twelve vital reasons why the EU has already ensured that it cannot offer a proper Canada-style deal at all. This is because the UK Government has so far acquiesced in a sequenced negotiating process in such a way that the desired Canada style-deal is unobtainable, unless and until the WA (and its NIP) is fundamentally altered or rejected. Otherwise, the UK will be accepting aspects that denude any ultimate deal to such an extent that inevitably it will fall far short of what the EU has agreed with Canada. For example, Canada is not subject to ECJ jurisdiction in any form nor is it subject to EU State aid control.

Therefore, whilst there is no doubting the Prime Minister's desire to achieve a Canada-style deal that is at least equal to the deal Canada secured, such an outcome will be all but unachievebale if the WA is left in place. Far from being able to achieve the much vaunted 'Canada plus, plus' deal, at best the UK will be able to achieve only a 'Canada minus, minus' deal.

Unless all the areas identified in this and an earlier Centre for Brexit Policy paper 1 are stripped out from the WA, the only way to achieve the UK's ambition is by resiling from the WA/NIP and conducting a negotiation as a sovereign nation, on a par with Canada, that provides for an invisible north-south Irish border in one of the two ways we have explained previously.

Even with this more ambitious approach, the UK would not be negotiating for a deal in the financial and other service sectors, thereby ignoring 80 per cent of our economy. This would hardly be a negotiating triumph. For, if the deal toward which we seem to be heading is done, it will give the EU the one big thing they want: tariff free access into the UK market for the EU's huge goods trade surplus. It would abandon the goal of access for UK financial and professional services into the EU market. And it might not (if reports are correct) even match the trade benefits of the existing Canada deal, which would deliver real value to the UK, such as home country certification and wide cumulation of origin. At the same time, such a deal would lock the UK into the negative aspects of the WA and NIP to which Canada is not subjected.

Once locked into such a deal, it is difficult to see what negotiating leverage the UK would retain to improve its situation in future. So, whatever short term pressures come from the COVID crisis, we should not do a deal that we would regret bitterly for years to come - on a short-term, but erroneous, presumption that something is better than nothing.

Through cynical and unpleasant manoeuvring (during the May government), the EU has so far boxed the UK negotiators into an unambitious corner, and the UK needs to punch its way through the paper walls to reach a proper outcome.

Recently, UK negotiators have managed to get the attention of EU member-states and to communicate the vital message that the UK will not agree to the ludicrous terms EU negotiators were hoping they might achieve. It is now time for the UK's negotiating team, and the Ministers to whom they report, to change the ask so as to propose a reasonable, win-win outcome. They must use all their negotiating skills to ensure they succeed in communicating that, from a UK perspective, it's either this, or nothing at all.

In practice, there is an objectively reasonable outcome that the EU cannot deny, once it accepts there is no outcome that might be achieved based on some of the absurd thinking its officials appear to have pumped themselves up to believe. The next section of the paper explains in depth the precise reasons why the 'future relationship agreement' as currently being negotiated is so inferior to the desired 'Canada-style relationship'.

TWELVE REASONS WHY THE EU CANNOT OFFER AN ACCEPTABLE CANADIAN DEAL

To many observers, it has seemed strange that previous offers of a 'Canadian-style' deal by then EU President, Donald Tusk, as well as Chief Negotiator, Michel Barnier, have been taken off the table. Many will remember the 'waterfall chart' presented by Michel Barnier in December 2017 that concluded a 'Canadian-style FTA' was the only logical outcome of the negotiations. Why this reversal?

The answer to this conundrum is that, subsequently, the WA and the NIP were negotiated. For the same reasons as explained in this paper, the EU is well aware that the provisions of the WA and the NIP makes offering a 'Canadian-style' deal impossible, as long as the WA/NIP remain in force. This provides the strongest possible argument for why the UK must fundamentally alter or reject the WA/NIP.

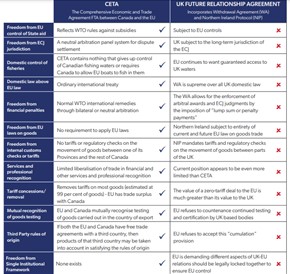

This section analyses the provisions of the existing Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the EU - ie, the 'Canada-style relationship' to which the UK Government aspires. See Annex A for a summary of the existing provisions of CETA. Specifically, the following sections compare the current Canadian relationship with the EU under CETA with the UK's projected relationship whereby the WA/NIP would continue to be operative alongside the UK-EU FRA. There are twelve critical ways in which the benefits that Canada enjoys under CETA would be degraded for the UK in such a scenario. These lead to negative effects on:

- UK sovereignty

- The EU-UK trading relationship

- Governance of the relationship

NEGATIVE EFFECTS ON UK SOVEREIGNTY

Crucially, seven of the twelve ways in which the WA/NIP would degrade CETA have a direct negative impact on the sovereignty of the UK across a wide range of issues. These lead to the UK remaining subject in important areas to de-facto colonial laws of the EU on 1 January 2021 if the WA/NIP continues in force.

Thus, the proposed FRA in conjunction with the WA/NIP would be inferior to CETA in the following ways:

Canada is not subject to EU State aid control. CETA contains provisions simply reflecting WTO rules against subsidies that distort international markets. By contrast, the UK would be subject to nonreciprocal State aid controls by the EU under the NIP and these extend into Great Britain (GB). Under the WA, the UK has no right to prevent damaging EU State aids that interfere with industries whether in NI or GB; and as regards NI is prevented from imposing countervailing duties under WTO rules to protect NI industries against EU State aids. It remains to be seen what may emerge separately in the FRA on State aid control over the UK.

Canada is not subject to ECJ jurisdiction in any form. CETA contains a neutral arbitration panel system for dispute settlement, and Article 29.3 permits the parties, as an alternative, to use the WTO disputes system where the dispute falls within WTO jurisdiction. By contrast, the UK would be subject to the long-term jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) direct jurisdiction will cover laws on

- The making and trading of goods within Northern Ireland (NI)

- Customs and other trading rules between NI and GB and NI and the EU

- EU State aid rules within NI and across GB if a measure is capable of affecting trade between NI and the EU

- The UK's vast financial obligations to the EU created by the WA

- The rights of EU citizens in the UK (in cases begun before the end of 2028)

Even where direct jurisdiction does not apply (for example in EU citizens' rights cases begun after 2028) a remarkable clause in Article 174 of the WA requires a bilateral arbitration panel to refer any question of EU law to the ECJ and to be bound by its decision. This clause means that the ECJ rather than the arbitration panel will continue to "interpret" the rules on the rights of EU citizens in the UK for their lifetimes.

The EU asserts that only its own court should be allowed to decide questions of EU law if they come up under international agreements. This assertion is contrary to general international treaty practice, under which neutral international tribunals rule on all issues, including (if relevant) the internal laws of the treaty parties. The ECJ is now, of course, a wholly foreign court to the UK, rather than a multinational court in which the UK is a participating member.

Logically, if the EU were to claim a special privilege that its own court must interpret EU law, then Canada would want all questions of Canadian Federal law referred to the Supreme Court of Canada. Unsurprisingly, CETA contains no provision similar to Article 174 of the WA, and the EU has failed to impose such a clause on any other of its trade treaty partners: which the exception of the desperate former Soviet republics of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia.

Unlike CETA, the WA excludes recourse to the WTO disputes procedures or any other procedure outside those laid down in the WA itself. It remains to be seen whether this clause will be carried over into the FRA. It also remains to be seen whether or not the FRA will involve an expansion of ECJ jurisdiction beyond that set out above.

Canada does not give the EU access to its fishing waters under CETA. CETA Article 24.11 contains mutual obligations between Canada and the EU to cooperate on measures to prevent overfishing and selling of fish illegally caught in each others' waters. However, CETA contains nothing that gives up control of Canadian fishing waters or requires Canada to allow EU boats to fish in them. The EU agreed to eliminate 95.5 per cent of its tariffs on fisheries products upon entry into force of CETA and 4.5 per cent of the tariffs within 3, 5 or 7 years, and Canada and the EU's fish inspection regulations are accorded mutual recognition as satisfying each other's health requirements on imported fish.

The fact that fish from Canadian waters are imported duty free into the EU and its fish inspection regime is recognised as satisfying EU health standards demonstrates that the EU's demand is absurd and unjustified that its boats should be allowed access to UK fishing waters in return for EU market access.

Canada is not required to give direct effect or supremacy to CETA under its laws. Under Canadian law, CETA is simply an ordinary international treaty and an ordinary Act of Parliament was passed to give effect to it internally within Canada. That Act like all Canadian Acts of Parliament is subordinate to the Constitution. By contrast, Article 4 of the WA requires that it (together with its Northern Ireland and other Protocols) must be given direct effect within UK courts and further, must be made supreme over all laws of UK origin including Acts of Parliament. This obligation has been duly enacted into law via section 7A of the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018, which was inserted by the EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020.

It remains to be seen whether the FRA will contain clauses requiring that its provisions also be given direct effect and supremacy within UK law. Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement Implementation Act of 2017. Indeed, section 8 of that Act explicitly states that no causes of action arise and no proceedings may be brought under the sections of the Act which implement CETA without the consent of the Attorney General of Canada.

Canada is not subject to fines and financial penalties for breaches of CETA. CETA is a normal international treaty that contains neutral means of dispute settlement, either via a bilateral arbitration panel under a neutral chairman or via the WTO disputes settlement system. These give rise to normal international remedies for their enforcement.

By contrast, the WA contains draconian provisions for the enforcement of arbitral awards by the imposition of "lump sum or penalty payments" under Article 178, and confers similar powers on the ECJ against the UK, a non-member State, by making the UK subject to Article 260 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU). Such powers to impose financial penalties are completely unprecedented in international trade agreements, including the EU's trade and association agreements with other countries. Such powers are not to be found even for example in the EU's Association Agreements with the former Soviet Republics of Ukraine, Moldova or Georgia and they are particularly egregious when in the hands of a foreign court that has no UK participation. It is not clear whether or not this draconian system of financial penalties will be extended into the FRA.

Canada does not have to apply EU laws on goods within one of its Provinces, effectively restricting inter-Provincial trade. This contrasts with the NIP, under which the whole corpus of EU single market laws relevant to the making and marketing of goods must be applied within NI, together with future changes to those laws. It would be unthinkable for Canada to agree to a trade treaty in which one Province was subjected to a different regulatory regime than the others.

Canada does not have to impose tariffs or regulatory checks on the movement of goods between one of its Provinces and the rest of Canada. A review of CETA from end to end reveals the absence of any such provisions, which in any case would be contrary to the Canadian Constitution. Section 121 of the Constitution Act 1867 says: "All Articles of the Growth, Produce, or Manufacture of any one of the Provinces shall, from and after the Union, be admitted free into each of the other Provinces."

Inter-Provincial trade is one of the key pillars of Canada's federal union. Canada would not countenance an international treaty that undermined this principle. The Canadian Free Trade Act of 2017 was precisely designed to further eliminate any existing barriers to inter-Provincial trade. This provision of the Canadian Constitution is remarkably similar to, and may historically be based upon, Article VI of the Articles of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland which says: "The subjects of Great Britain and Ireland shall be on the same footing in respect of trade and navigation, and in all treaties with foreign powers the subjects of Ireland shall have the same privileges as British subjects. From January 1, 10p0801, all prohibitions and bounties on the export of articles the produce or manufacture of either country to the other shall cease."

NEGATIVE EFFECTS ON THE EU-UK TRADING RELATIONSHIP

Four further reasons, numbered 8-11 below, explain why the proposed FRA would have a serious negative impact on the UK's trading relationship with the EU. So much so that the deal would be much worse from a trading perspective than the CETA agreement - and not worth having. This conclusion arises just from looking at the trade terms alone while ignoring points 1 to 7 above, and ignoring the possible additional State aid and "level playing field" restrictions that the EU is seeking to include within the FRA.

Importantly, such a one-sided trade deal would give the EU what it wants - ie, tariff free entry of its huge goods surplus into the UK market without the UK receiving corresponding benefits in either goods or services trade or vital agreements to overcome non-tariff regulatory barriers or rules-of-origin on UK exports to the EU. By giving the EU its "asks" (the EU cleverly has not characterised them as such, or even admitted it has any asks) without insisting on the quid-pro-quos now, the UK would be giving away the necessary negotiating leverage to improve these terms in future.

It would be far better to trade on WTO terms beginning on 1 January 2021 and seek to negotiate a more balanced trading relationship with the EU subsequently, when UK sovereignty has become a 'fact', so no sovereignty issues can be muddied into the trade discussions. At the same time, the EU member states would begin appreciating the harm a WTO relationship imposes on them.

Furthermore, EU member states would start to appreciate how their interests are divergent, not least given the structural flaws in the Eurozone architecture, which create lopsided benefits for the north (and corresponding detriments to the south), as well as the need for the UK's assistance in keeping its Eurozone show on the road.

Potential employment of WTO remedies by the UK for trade dumping and unfair subsidisation would require the imposition of tariffs for the northern Eurozone to remove the competitive distortions, but it would not correct the distortions in the other direction that are to the detriment of the south. Therefore, one would expect southern states, when they appreciate this bald fact, to become unsettled in their faith as to the fairness or acceptability of the entire EU structure.

In addition, the EU's competitive position would be severely injured if the UK - without an FRA or any predictable or reliable agreement with the EU for financial services - were to apply international Basel standards properly to financial business transacted from London with EU financial institutions (including subsidiaries of global institutions). For example, this would mean the EU's (including the Eurozone's) financing costs would increase, the viability of EU banks would be threatened (at least in the short term) and southern states might question still more why they were suffering financially for the sake of the aspirations of a couple of member states to have a small number of financial services jobs located locally (in newly formed subsidiaries of global financial institutions, to act as new, and unnecessary, middlemen).

The four points below explain in detail why the proposed FRA would be so inferior to CETA that the actions discussed above would be appropriate.

CETA provides for limited liberalisation of trade in financial and other services and recognition of professional qualifications. This is an area where it was originally hoped (remember the talk of a "Canada plus" deal) that the FRA with the EU would be better than CETA.

This is particularly important to the UK, given that we are a uniquely services-based economy and are the second largest exporter of commercial services in the world, second only to the USA. We have a huge trade deficit in goods with the EU, but a small surplus in services. A balanced FTA between the UK and the EU therefore should provide for extensive liberalisation of the export market for services from the UK to the EU, in return for liberalisation of the goods import market into the UK.

Unfortunately it appears that the FRA now being negotiated by the UK Government will not exceed, and may not even be as good as, the services and professional recognition provisions of CETA. It is quite clear that a services deal can be done legally, with relative ease. Enhanced Equivalence shows the path for the complex and important financial services sector. If it is properly drafted and the UK's financial services laws and regulations are recognised in whatever form they take from time to time, so long as the UK (unlike the EU) respects the international Basel regulatory standards, then the result would be attractive for the UK and protective for the EU, with its structural problems in the Eurozone.

Executing on this politically will involve the UK identifying and applying the extraordinary legal leverage available that results from the half-built Eurozone. This is a point the EU has chosen to ignore and yet is one that cannot be glossed over. The trade dumping and unfair subsidisation resulting from the structure, delivering lopsided benefits to the northern Eurozone and creating unmanaged financial risk, are factors that cannot be overlooked by the UK if it is to protect its interests and those of its businesses and consumers.

Canada does not give tariff concessions to the EU worth over double the EU's tariff concessions to Canada. CETA provides for the removal of tariffs on most goods (said to be ultimately on 99 per cent of goods). According to Commission figures, EU trade with Canada over the last few years has generally been in surplus both as regards goods and services.

However, any imbalance in CETA on the value of tariff concessions is dwarfed by the grotesque imbalance in the respective values of the tariff concessions being offered by the UK and the EU under a zero-tariff FRA. Using the EU's common external tariff as the starting point, the value of a zero tariff concession on UK exports to the EU on 2015 trade volumes was calculated at £5.2bn per year, whereas the value to the EU of zero tariff concession on its exports to the UK was calculated at £12.9bn.

The reasons for this huge discrepancy are twofold. First, the value of the EU's goods exports into the UK is much greater (nearly double) than the value of the UK's goods exports into the EU27. Secondly, the EU's exports to the UK are concentrated in high tariff sectors (vehicles, food and agricultural products, clothes and textiles) as compared with the UK's exports that on average are in much lower tariff sectors.

The precise figures in this study based on 2015 trade figures need adjustment both to bring the figures on the underlying trade up to date, and also to calculate the value of the UK's zero tariff concession based on the UK's post-Brexit MFN tariff schedules rather than on the EU common external tariff. However the overall picture remains valid, which is that the value of a zero tariff deal to the EU is much greater than its value to the UK, probably more than double. Not surprisingly, the EU is very keen on this aspect of the FRA.

What is less clear is why it should be in the UK's interest to give this massively one-sided tariff concession to the EU, while not insisting in return on home country certification, diagonal (third country) cumulation of origin, and market access for UK services exports.

0

Canadian exporters can take advantage of "home country certification" that exports comply with EU standards. CETA has a "Protocol on the mutual acceptance of the results of conformity assessment" that provides for the EU and Canada mutually to recognise testing of goods carried out in the country of export, in order to avoid the need for double testing within the EU (or vice versa). Article 3(2) of that Protocol states that: "The European Union shall recognise a third-party conformity assessment body established in Canada as competent to assess conformity with specific European Union technical regulations, under conditions no less favourable than those applied for the recognition of third-party conformity assessment bodies established in the European Union", provided that certain conditions are met.

By contrast, the EU has refused to countenance continued testing and certification by UK based bodies for avowedly protectionist reasons: "European Commission rejects call for UK testing labs to certify products for export to EU market" (Telegraph, 14 May 2020). There could not be an FTA more ripe or appropriate for home country certification than the FRA. There is an existing vast range of certification required under EU single market law within which UK based certification bodies are familiar and skilled at carrying out.

There is no objective reason why they should suddenly lose their capacity to perform these tests and certifications from 1 January 2021. The EU's refusal to countenance home country certification in the FRA seriously degrades the value of the overall agreement to the UK. For example, UK based car manufacturers would have to get their cars certified and tested twice in order to export into the EU, a needless expense that would also cause delays affecting whole logistic chains.

Canada benefits from "cumulation of origin" under FTAs with third countries. CETA's Protocol on Rules of Origin, Article 3(8), provides for so-called "diagonal cumulation" of origin. This highly technical but very important subject means that, if both the EU and Canada have free trade agreements with a third country, then products of that third country may be taken into account in satisfying the rules of origin that regulate tariff free access into each other's market.

For example, 'rules of origin' entitling cars to be imported duty free under CETA require that 55 per cent of the value of the car must be created within the free trade partners. The purpose of this rule is to prevent a car that is, for example, 90 per cent created in China from being imported into Canada, having another 10 per cent work done on it to complete, and thus what is in essence a Chinese car benefiting from the zero per cent tariff concession under CETA.

Both the EU and Canada have free trade agreements with Japan. "Diagonal cumulation" means that parts of Japanese origin may also be taken into account as counting towards the 55 per cent threshold at which the finished car becomes entitled to be exported tariff free to the EU under CETA.

This cumulation of origin from third countries with which both partners have free trade agreements is routinely agreed by the EU and is embodied in the "Regional Convention on pan Euro Mediterranean preferential rules of origin" (PEM Convention) that contains all the European and near-European (North African) countries with which the EU has FTAs. The PEM Convention also allows for cumulation between all signatories to the agreement.

Despite this, and without objective justification, and despite offering such cumulation deals to, for example, Japan and Singapore, the EU has refused to offer the same arrangement to the UK. As reported in The Express, 19 June 2020,10 'A senior EU official said: "This is an area where we do not in any way see any margin of compromise. We do not believe that it is in the EU interest."'

This is likely to degrade the value of the FRA to the UK seriously and cause particular problems for the car industry. Given that the EU is made up of 27 countries, its car plants will find it easier to make up the required 55 per cent of value from parts sourced within the EU than it will be for car plants within the UK to achieve 55 per cent content locally. This may be a particular problem for Japanese car manufacturers based in the UK who are not allowed to use content from Japan to count towards the threshold despite the fact that there is an FTA in force between the EU and Japan that allows the parts to be imported into the EU tariff free.

NEGATIVE EFFECTS ON GOVERNANCE

The EU is attempting to impose a governance structure on any future deal that would provide them with undue control over the UK and make it almost impossible to renegotiate individual aspects of the agreement in future - as Switzerland has discovered to its cost.

Canada is not subject to a "single institutional framework". CETA is a comprehensive agreement covering the trade and trade related fields that it covers, but it has not been bundled together with other EU-Canada agreements into a single institutional framework. By contrast, a demand made by the EU is that the FRA shall be governed by a single institutional framework and that different aspects of UK-EU relations (eg, trade, security cooperation, extradition) should be locked together legally. This is a technique favoured by the EU in order to exercise control over counter parties and should be resisted at all costs. For example, when the Swiss people voted by referendum to curtail free movement of persons from the EU, they found that the Swiss-EU agreement on free movement of persons had been locked to the Swiss-EU agreement on free trade in goods, so that they could not terminate or renegotiate free movement without bringing tariff-free access to the EU market for goods to an end. The EU is currently attempting to lock Switzerland even more tightly into a formal single institutional framework.

ANNEX A - KEY PROVISIONS OF CETA

CETA removed all tariffs on 98 per cent of traded goods. The areas where tariffs remain mostly comprise sensitive agricultural products like dairy. These tariffs were either eliminated instantly or gradually within 3, 5 or 7 years.

On non tariff barriers, CETA's chapter on technical barriers to trade (TBT) builds on the key provisions of the WTO TBT (Technical Barriers to Trade) Agreement. It contains provisions designed to improve transparency and foster closer contact between the EU and Canada in the field of technical regulations. Both sides agreed to strengthen cooperation between their standard setting bodies as well as their testing, certification and accreditation organizations. A separate protocol improved the recognition of conformity assessment between the Parties. It provides for a mechanism by which EU certification bodies will be allowed according to the rules applicable in Canada to certify for the Canadian market according to Canadian technical regulations and vice versa.

The CETA's Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Chapter preserves the rights and obligations of the EU and of Canada under the WTO SPS Agreement. For meat products, the existing EUCanada Veterinary Agreement was integrated into CETA. The Parties agreed to simplify the approval process for exporting establishments and work on minimising trade restrictions in the event of a disease outbreak. In the area of plant health, CETA sets new procedures to facilitate the approval process of plants, fruit and vegetables. A work programme has been put in place so that in the future, CETA will also cater for an EU-wide assessment and approval process for fruits and vegetables. For all product categories, the parties agreed to establish fast track procedures. CETA will further streamline approval processes, reduce cost and improve predictability of trade in animal and plant products. It's important to note that CETA does not amend either the European or the Canadian SPS rules. All products still need to fully comply with applicable sanitary and phytosanitary standards of the importing Party.

Regarding customs and trade facilitation, CETA will simplify and render more transparent the customs clearance of goods in order to facilitate bilateral trade and reduce transaction costs for importers and exporters. It sets common principles and provides for enhanced cooperation and exchange of information between the customs authorities of the EU and Canada with a view to facilitate import, export and transit requirements and procedures. Provisions on transparency ensure that legislation, decisions and administrative policies, fees and charges related to the import or export of goods and governing customs matters are made public and that for new customs-related initiatives interested persons have an opportunity to comment before their adoption. Importantly also, Canada and the EU undertake to apply simplified, modern and, where possible, automated procedures for the efficient and expedited release of goods. This will incorporate risk management, release of goods at the first point of arrival, simplified documentation requirements for the entry of low value goods and pre arrival processing. This material should be advantageous for SMEs.

CETA achieves less on the liberalization of services; however, it does provide room for recognition of professional qualifications and licenses of services providers. Under CETA the EU guarantees to Canadian service providers its current level of liberalisation in many sectors through an annex of reservations. For critical and sensitive areas or sectors CETA safeguards the ability of the EU and Member States to introduce discriminatory measures or quantitative restrictions in the future by specifying these areas or sectors in their reservations annex. This flexibility concerns public monopolies and exclusive rights for public utilities that the EU and its Member States will be able to operate at all levels of government. – With regard to the supply of a service through the temporary presence of natural persons (Mode 4 under the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services), CETA contains provisions for intra corporate transferees to facilitate the activities of both European and Canadian professionals and investors. Whenever investment is liberalised, inter corporate transferees are guaranteed access. Furthermore, both Canada and the EU undertake to allow companies to post their intra corporate transferees to Canada for up to 3 years regardless of their sector of activity. In addition, the agreement guarantees that intra corporate transferees may be accompanied by their spouses and families when temporarily assigned to subsidiaries abroad. Natural persons, who provide a service as so called 'contractual service suppliers' or 'independent professionals' will be able to stay in the other party for a period of twelve months instead of 6 months. CETA contains an extensive set of mutually binding disciplines with respect to domestic regulation ensuring fairness, equitable treatment with domestic suppliers and transparency for licensing and qualification regimes.

CETA further establishes a framework for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications and determines the general conditions and guidelines for the negotiation of profession specific agreements, or mutual recognition agreements (MRAs), typically in regulated professions such as lawyers.

On foreign investment, CETA includes material on the EU's new, innovative approach to investment and associate dispute settlement. A new article confirms that the EU and Canada fully preserve their right to regulate. This gives a clear instruction to tribunals regarding the interpretation of the investment protection rules. These rules have been also clearly defined. For example, the rule of Fair and Equitable Treatment incorporates a closed list of the elements that could give rise to a violation. CETA also incorporates an Annex on Indirect Expropriation that defines what situations constitute an indirect expropriation. It is important to note that all investors in the EU already enjoy the same or higher guarantees under EU law and the laws of the Member States. In this respect, CETA provides basic guarantees to Canadian investors in the EU, but not a higher level of protection. The investment chapter incorporates all the essential elements of the EU's new approach on investor state dispute settlement, involving a permanent tribunal as well as an appeal system.

On government procurement, CETA eliminates a major asymmetry between the EU and Canada given that the EU was de facto already open to Canadians under the terms of the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), including at the sun federal level, while in Canada the access for foreigners was very limited. The Canadian commitments now cover the procurement of federal entities, provincial and territorial ministries and most agencies of government. The text of this chapter based on provisions derived from the GPA. There is additional detailed material on a single electronic procurement website, which corresponds to existing intra EU arrangements.

Contact us

246 Linen Hall, 162-168 Regent Street

London W1B 5TB

Director : Robert Oulds MA, FRSA

Founder Chairman : Lord Harris of High Cross