Bruges Group Blog

Robert Jenrick's talk to the Bruges Group was widely reported. Please see below links to the stories: The GuardianTory candidates must pledge support for leaving ECHR or stand down, says JenrickShadow justice secretary demands prospective MPs sign contract saying they stand for 'Conservative values' UK politics The TelegraphRobert Jenric...

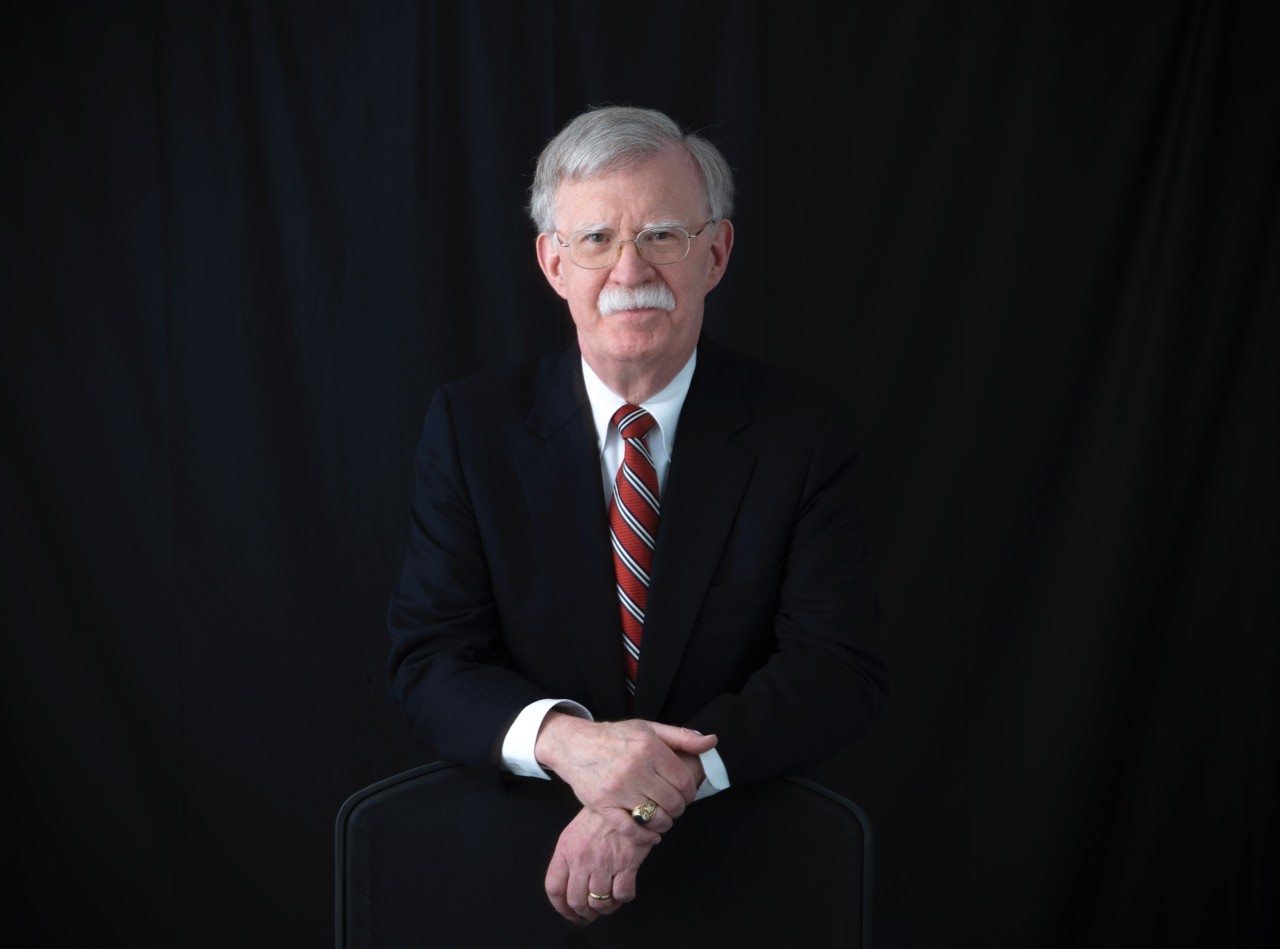

Monday, 1st September 2025 6pm until Late The Speakers; Ambassador John BoltonAmerican Ambassador to the United Nations, Under-Secretary of State for Arms Control, and National Security Advisor.&Lord Hannan of KingsclereBritish writer, journalist and politician. Speakers will discuss: International relations, geopolitics, trad...

Wednesday, 16th July 2025 6.30pm until Late The Speakers; Andrew Griffith MPShadow Secretary of State for Business and TradeRichard Tice MPDeputy Leader of Reform UKRoger BootleChairman of Capital Economics&Professor Tim Congdon CBELeading economic commentator will discuss immigration and Britain's position in the world Speakers wi...

Brexit Success - the changes that will transform Britain's role in the worldMake Brexit Great Again AGENDA:Registration and Coffee: 10.30amMorning Session: 11am – 1pmLunch: 1pm – 2pmAfternoon Session: 2pm – 4pmRefreshments: 4pm - 4.15pmEvening Session: 4.15pm – 6pm Saturday, 1st March 2025 10.30m until 6pm Wine and nibbles served f...

Santa's Sovereignty Spritz A Festive Toast to Freedom Monday, 2nd December 2024 6pm until Late Wine and nibbles served from 6pm until late Location Pall Mall RoomArmy & Navy Club36-39 Pall MallSt. James'sLondon SW1Y 5JN

The unthinkable has happened, a conventional war on the continent of Europe, but the military has been slow to adapt. Yes, Europe has seen bloodshed since 1945; terrorism, militias fighting in Balkanised countries, unmatched airpower imposing diplomacy on those breaching the peace. However, our security cannot be taken for granted. The invasion of ...

Reform and Trump have similar objectives. These have generally been mischaracterised as far right, but this new wave of populism is more about nationalism vs globalism than it is about left vs right. It is primarily concerned with what is seen as the theft of our national democracy in pursuant of global goals by international bodies that include th...

16th December 1944, western Europe. Hitler launches his last great gamble in the west. Fanatical Nazi soldiers were unleashed on unsuspecting Americans resting far away from where they thought the fighting would take place. The Battle of the Bulge was underway. This film explains the key role that the controversial victor of El-Alamein, Field Marsh...

https://amzn.eu/d/7V5gojUWar is again on the agenda. Different versions of authoritarianism are set against each other driving the rival camps from crisis to conflict. BRICS verses Build Back Better is the new divide. The principles which gave Britain and her allies victory in the last great conflagration have largely been forgotten. With...

There's been much talk of a swing to Labour in recent months - the Tories, by some measure appear to be 20 points behind. We must ask ourselves, what's behind this polling and how is it being conducted. There are some worrying signs. From our statistics, one thing is for sure: There is no "swing to Labour" - or at least, not a sign...

The National Interest Advancing freedom, Brexit, and the British national interest. Speakers include;Sir Christopher Chope MP, Bernard Connolly, Barry Legg, Barney Reynolds, The Rt Hon. the Lord Lilley, PC and Sir Bill Cash MP. Location:Pall Mall Room, Army & Navy Club36-39 Pall Mall, St. James's, London SW1Y 5JN Speakers ...

As part of the Bruges Group's Climate Change Programme, we present this paper on the True Science on Climate Change by Keith Shotbolt. Download PDF File Here

Greenhouse Emissions say, without Greenhouse Gases, Earth becomes -18 C ball of ice.Science says not so.K-T balance graphics show a 396/333/63 GHE energy loop.Science says bad math & badder physics.GHE says Earth upwells "extra" energy as a BB surface. Science says not possible. No Greenhouse Emissions, no Greenhouse Gas hea...

The Bruges Group is pleased to republish this article by Barnabas Reynolds Brussels' rules are prescriptive and controlling, and are holding back British growth The Prime Minister must restore Britain's sovereignty over our laws The Government is seeking the power to remove some of the vast swathes of EU-inherited law by the end of 2023 in it...

The EU likes to sell itself as the high priests of the 'rules-based' system, as the bedrock of financial stability worldwide. So much so that 'stability' was one of the main arguments of the remain side back in 2016 - and remains a prominent argument for rejoining today. In this Bruges Group publication, "The shadow liabilities of EU member s...

This paper was written in November 2022 by: Stuart Agnew. MRAC (Agricultural science) Roger Helmer. M A Cantab (Mathematics) It is published by the Bruges Group as an Important contribution to a debate we should be having. OVERVIEW Within the last 20 years a belief has become established that the planet is imminently destined for catastrophic clima...

Although Brexit and the free trade agreement initially disrupted and confused UK-based business operations due to the UK's dominant role in cross-border online distribution and sales with other European countries, things are finally looking up in the long run. A study published by the Board of Trade stresses the enormous prospects that digital trad...

Author Jeremy Nieboer spoke to The Bruges Group's October Conference on his latest book, Nature's Gift, on his book's central thesis on climate change, the greenhouse effect, and saturation. The most important issue relating to climate change, Nieboer argues, is saturation, and he goes deeper into its importance in debating this issue and bringing ...

The Bruges Group had the pleasure of hearing from the distinguished Mark Francois, Chair of the European Research Group and MP for Rayleigh and Wickford - a longtime advocate of Brexit with a significant impact on the UK's direction in Europe, at The Bruges Group's Conference in October. His bestselling book, Spartan Victory, was an insider's ...

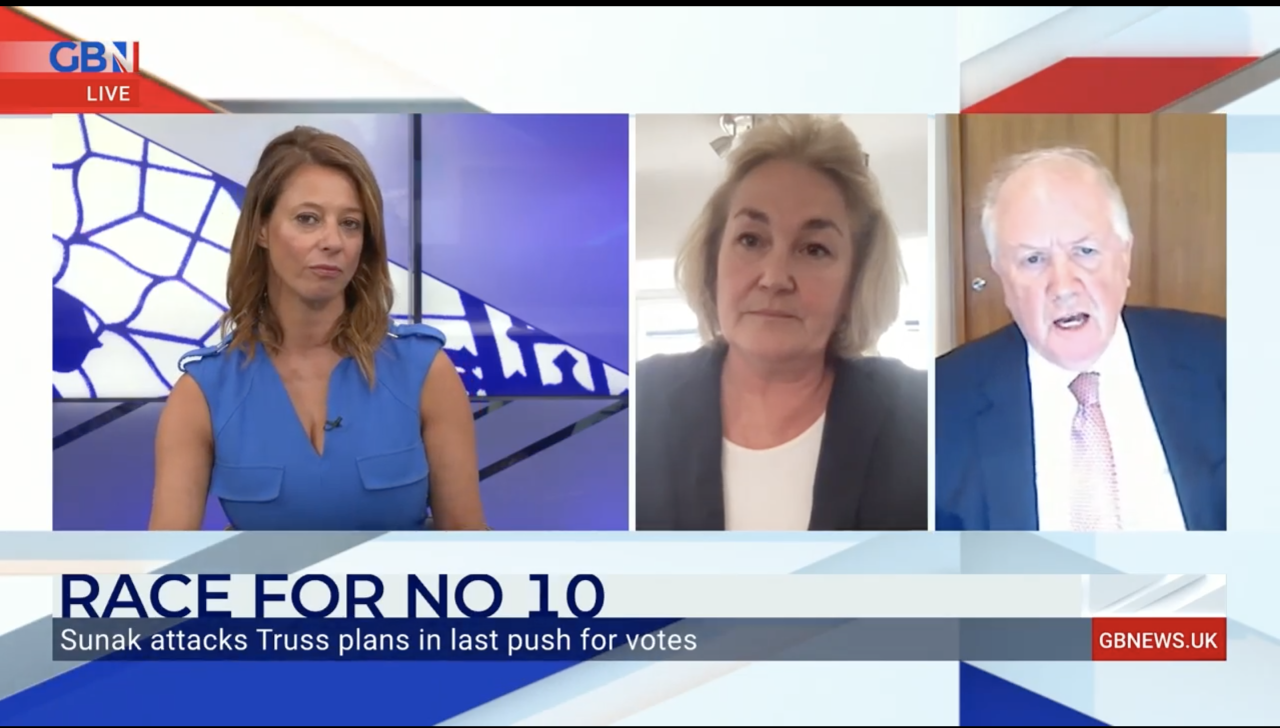

Bruges Group Chairman Barry Legg appeared on GB News' The Briefing, hosted by Gloria de Piero, to discuss the cost of living crisis and the pay of FTSE 100 Chief Executives, joined by former Labour MP Natascha Engel. The discussion can be found here. Reacting that the average pay of FTSE 100 Chief Executives has jumped by 39% to £3.4 Million, host ...

The following analysis by Ben Habib is reprinted from: https://www.newsletter.co.uk/news/opinion/ben-habib-we-are-being-hoodwinked-again-by-the-northern-ireland-protocol-bill-3750685 Ben Habib is a Newspaper Columnist and former Brexit Party MEP I am having a profound sense of déjà vu. In 2019 I said the Prime Minister's oven ready deal was a...

nologThe COVID-19 pandemic had an unprecedented impact on companies across the world. In the two years since initial lockdown, far too many businesses continue to struggle to make a comeback. The Prime Minister of England has officially urged people to go back to their offices and normal work environments. His goal is to get everyone back to living...

Some people who start a business dream of it becoming an enterprise that is passed down through generations. While this is true for some companies and families, it can also be a fraught ambition. Families can be dysfunctional, and when that dysfunction is transferred to the workplace, it can be catastrophic for the business. Furthermore, there is n...

Boris Johnson is often dismissed as a know-nothing on economics, and Rishi Sunak prides himself on being rather good at it. In his generally excellent recent Mais lecture, the Chancellor set out his vision for the UK economy. He aims for freeing up markets, improving regulation, and cutting taxes to incentivise investment, training and R...

Toothless EU 2014 embargo on export of weapons to Russia finally enforced on 8 April 2022 Removal of loophole covered up by EU – not mentioned in latest sanctions press release In our previous report of 25 March on EU arms sales to Russia between 2014-2020 we revealed how a clause allowed weapons contracts to continue to be fulfilled if they ...

Crypto regulations would have been identical for both the EU and the UK. However, the Brexit game brings chaos, and hence the crypto regulations, including the famous Bitcoin and Ripple, are independently defined, yet few sections overlap. This guide will bring some light on the cryptocurrencies regulations in the United Kingdom and European Union....

US states courted for deals on financial services after US tariffs on steel and aluminium lifted. A look at the improving UK trade with US and Canada While all eyes have been on the possibility of a large bilateral deal with the US, the two governments have been reaching across the pond to strike small deals that amount to great improvements ...

RAF deploys fighter jets and Expeditionary Air Wing personnel to EU's Romania. Once again, Brexit Britain flies to the protection of the EU On Saturday the Ministry of Defence announced that British Typhoon jets and Royal Air Force personnel are deploying to Romania. They will operate as part of NATO's 'Air Policing mission' for the Black Sea...

Voters are looking at Rishi Sunak's chaotic mini-Budget and concluding: the party stands for nothing at all. Every so often, a member of the Question Time audience manages to capture the current mood. It happened when an elderly gentleman told a bickering Nigel Farage and Eddie Izzard to "shut up" during a programme filmed in the run up to th...

While others close their Russian doors, French tills in Russia keep ringing. French companies find reasons to do business in Russia while British companies pull out Economic sanctions from Western nations were meant to send a message to President Putin: Stop the war and withdraw from Ukraine. The French are ignoring world opinion. Many busine...

ONE of the great lines of the proponents of renewable power is that the input energy (mostly wind and solar) is free, therefore producing renewable energy is less expensive that from fossil fuels. Even though wind isn't always available and therefore needs some back-up power – usually gas fired – the more wind generation there is the less gas will ...

The European Commission is the executive branch within the broader European Union or EU. It apparently intends to introduce the continent's own digital euro bill sometime during 2023. This would coincide with experimentation done by the European Central Bank with a retail version of central bank digital currency across the union. Movement Among Mix...

The current cost of living crisis and stagnating growth highlight the importance of a re-examination of our approach to tax, trade and business, writes John Longworth. During the pandemic, conspiracy theorists loved to talk about the "great reset" that would be orchestrated by the Davos-loving global elites. If the events of the past two weeks is a...

It is constantly claimed that the purpose of the Irish protocol is to prevent a hard border on the island of Ireland, but that is a lie. The real purpose is to disrupt the existing economic integration between Northern Ireland and Great Britain and instead promote integration between the province and the Irish Republic, and the chosen mechanism for...

Facts4EU.Org presents their review of the major Global Soft Power rankings in the world. Their analysis of these rankings covers every year from the first in 2010 until the latest for 2022. We reviewed the three emerging ranking systems that have over time become more and more detailed and analytical. We started with the Institute of Governmen...

By Professor Patrick Minford, CBE Patrick is the Chairman, Economists for Free Trade. He is Professor of Economics at Cardiff Business School, part of the University of Wales. Patrick is the author of The Cost of Europe, and Should Britain Leave the EU?: An Economic Analysis of a Troubled Relationship. Professor Minford is also a member of the Brug...

The case for a new Bretton Woods, Kevin Gallagher and Richard Kozul-Wright, paperback, 163 pages, ISBN 978-1-5095-4654-1, Polity Press, 2022, £9.99. Kevin Gallagher is Professor of Global Developmental Policy and Director of the Global Developmental Policy Center at Boston University. Richard Kozul-Wright is Director of the Division on Global...

Whether you're just starting out or already have an established business, you've most likely learned by now how important social media is in today's society, and specifically how important it is to maintain an active Instagram account. When you consider that Instagram has more than 1 billion active users and that about 90 percent of them follow at ...

It's clear that UK industry is in a period of adjustment post-Brexit. Despite the drop in FDI and disruptions like the global pandemic, there are nonetheless emerging industries where the UK has the potential for global leadership. The education technology (edtech) industry is undoubtedly one of them. 1. UK education pre-Brexit Prior to the Brexit ...

The coronavirus pandemic changed the landscape of the world economy almost overnight. Certainly, industries who before would see handsome turnovers year on year had their custom suddenly wiped out – or at least massive reduced. We are all aware of the biggest losers from Covid, as the effects of their misfortunes were all around for all to see. Mor...

Initial article on The Bow Group By Robert Oulds and Dr Niall McCrae "You'll own nothing, and you'll be happy" (World Economic Forum, 18 November 2016). Covid-19 is a crisis too good to waste for UN agencies and other transnational bodies. The coronavirus pandemic has led to governments around the world signing up to the 'Great Reset' designe...

President Trump will win big since Republican voters are super energised and are turning out in massive numbers to vote for him, on the other hand Democrat voters are not enthused by the incompetent and senile 'Sleepy' Joe Biden. The polls that predict Biden is winning the US election so far, which is already underway, assume that there's...

Moralitis, A Cultural Virus - these films are an antidote to the collective malady that is woke ideology. Moralitis is at the centre of the culture war and cancel culture, its the cause of deluded social justice warriors. Watch and read about how we can treat and prevent this disease, a mental pathogen; so that we can save our civilisation, freedom...

By Robert Oulds and Dr Niall McCrae, originally published on The Salisbury Review - https://www.salisburyreview.com/blog/chiswick-takes-the-knee/ On a sunny Saturday morning, the queue outside Waitrose on the main thoroughfare in Chiswick basked in a glow of self-satisfaction. Dozens of casually-dressed, trendy urbanites displayed their social...

Roland Vaubel Professor emeritus of Economics Universitaet Mannheim Germany Mr. Barnier seems to misunderstand the argument for maintaining a level playing field. The laws of a country, above all, ought to reflect the preferences of its people. It follows that the laws ought to differ between countries if, and to the extent that, the preferences of...

Originally published in The Critic by David Scullion https://thecritic.co.uk/the-government-split-over-free-trade/ The Government is committed to signing Free Trade deals. The Conservative Party's 2019 manifesto said as much, and added: "Our trade deals will not only be free but fair". The UK has just started trade talks with the United ...

In this enlightening new book, Robert Oulds and Niall McCrae examine the causes, symptoms and methods of prevention and treatment of 'moralitis', a delusional condition caused by cultural Marxism.The body politic has become infected. Like the growth of bacteria in a Petri dish, the subversive tenets of cultural Marxism have spread as a pinking of t...

Institute of International Monetary Research Analysis Professor Tim Congdon CBE is a member of The Bruges Group Academic Advisory Council A lot of interest has been drawn from my recent emails to my fellow macroeconomists and monetary analysts where I pointed out that bank deposits at US commercial banks soared in the fortnight to 2...

First published by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard in the Daily Telegraph https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2020/05/06/longer-brexit-transition-pointless-dangerous-plays-straight/ Sir Nick Clegg is right. The terms of the Brexit transition are intolerable. They were bad for one year. The arrangement becomes progressively more dangerous over time. ...

Following the speeches of Mark Francois MP and Andrea Jenkyns MP, we are delighted to publish Professor Tim Congdon CBE's presentation to the Bruges Group annual conference on March 7th 2020. The Demographic Fate of Nations Women need to have 2.1 children on average in order to replace the current generation. Suppose that they have less than ...

The Brexit Agreement and regulatory checks affecting Northern Ireland By Simon McIlwaine An aspect of the Prime Minister's withdrawal agreement with the EU causes much anxiety among supporters of the UK's withdrawal and Northern Ireland in particular. Whether or not there is going to be any kind of internal UK border is causing great concern i...

This article was initially published on BrexitCentral https://brexitcentral.com/why-the-brexit-party-maintains-that-boris-johnsons-deal-is-not-brexit/ by Brexit Party MEP, Ben Habib Ben Habib believes there is an "understandable desire amongst many Brexiteers to accept Boris Johnson's deal". Everyone is battle weary, but it is preci...

As I assume you know, the Benn Act, or more commonly known as the Surrender Act, isn't the most well thought out piece of legislation, as lined out by Chair of Lawyers for Britain Martin Howe QC at The Bruges Group 'Moment of Truth' event in Manchester during Conservative Party conference. This article will outline the loopholes that Boris Johnson,...

The Revised Political Declaration Introduction So far as we are aware the only material changes in the Withdrawal Agreement (Treaty) are to the NI Protocol, which means that the critical ECJ oversight and Art 184 link to the Political Declaration remain. I am told by UKREP that there are two changes to other Articles in the Treaty but they were una...

1. This Agreement – even without the 'Backstop' - will put the UK under the de facto jurisdiction of a group of 27 foreign powers, leaving the UK powerless to veto laws or procedures affecting the UK and its citizens. (Articles 4, 86, 87, 89, 132, 168, 174) 2. The EU27 can make decisions behind closed doors which can profoundly affect British busin...

It often thought that lobbying, the professional representation of private interests to governments and subsequent attempts to influence policy, was confined to industrial-like political powerhouses of Washington D.C., the capital of the free world, and Brussels, the de facto capital of the European Union. In the US, the currency within lobbying is...

Leaving the EU Brexit Hub Monday, 30th September 20191pm until 2.30pm With the speakers; Rt Hon Sir John Redwood MPFormer Secretary of State and serving Privy CounsellorRt Hon. Arlene Foster, MLALeader of the Democratic Unionist PartyRt Hon. Mark Francois MPEuropean Research Group& Martin Howe QCLawyers for BritainAGENDASpeeches and press confe...

Below is John Redwood's letter to Geoffrey Cox. The Attorney General has not yet replied, and he needs to.Given the government's difficulty in replying to this, John Redwood is re-issuing it and encourage all to circulate it more widely. The conventional media refuse to ask these questions of the government and supporters of the Agreement. De...

The 28 Leaver Conservative Members of Parliament who voted against Theresa May's 'Withdrawal' Agreement: Adam Afriyie Steve Baker John Baron Peter Bone Suella Braverman Andrew Bridgen Sir Bill Cash Sir Christopher Chope James Duddridge Mark Francois Marcus Fysh Philip Hollobone Adam Holloway Ranil Jayawardena Bernard Jenkin Andrea Jenkyns David Jon...

Britain was a leader in international trade for centuries, long before the EU was even thought of. As an EU member state, the UK cannot now trade on our own terms with the rest of the world. Decisions are made for us, based on the interests of the EU 28 - not the UK.Today, the UK is still a member in its own right of over 100 international organisa...

As Geoffrey Cox, Attorney General, advises: there is no internationally legal means of escaping the Backstop. 'The legal risk remains unchanged that if through no such demonstrable failure of either party, but simply because of intractable differences, that situation does arise, the United Kingdom would have ... no internationally lawful mean...

Can the same Bill be re-introduced having once before been rejected by the Commons? This question has profound implications for the future of our exit from the European Union. In normal times, when democracy appeared to be respected, if a Bill has been rejected it could not be reintroduced in the same parliamentary year. The overwhelming reje...

The backstop is illegal. When speaking with international lawyers they mention a number of difficulties that the EU will discover if they actually try to implement the backstop. The competence of the 'Withdrawal' Agreement to establish the backstop exceeds its lawful ability, it is Ultra Vires.Given indications from the President of the...

No other issue in recent history has been as divisive as Brexit. And after the historic leave vote in June 2016, the nation has been inundated with one doomsday headline after another — from economic devastation to the loss of trade, and investment. Despite all of these issues, however, Brexit is now closing in on its March 29 deadline day. Of cour...

Brexit - Our Future! With Rt Hon. Lord Lilley PC, Rt Hon. Sammy Wilson MP and Daniel Kawczynski MP Bruges Group Conference Morning Session - with Shanker Singham, Martin Howe QC, Andrew Bridgen MP and Ewen Stewart Afternoon Session - with Rt Hon. Mark Francois MP, Dr Gerard Lyons and Professor Patrick Minford Evening Session...

Amidst the political fallout in the UK following the government's controversial draft Brexit deal, an equally important development in Ireland went relatively unnoticed. During the ruling Fine Gael party's annual conference, foreign minister Simon Coveney confirmed that Ireland has no plans to prepare infrastructure for a hard border with the UK, e...

Analysis of Theresa May's Brexit proposal. Can the UK claim to be an independent state? Introduction The current draft of the agreement "on Withdrawal of the UK from the EU and EURATOM" (the "Agreement") can be found here... https://ec.europa.eu/commission/files/draft-agreement-withdrawal-united-kingdom-great-britain-and-northern-ireland-euro...

On 20th September 1988 Lady Thatcher made her seminal Bruges Speech. As Prime Minister famously said to the College of Europe in Bruges; "We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them reimposed at a European level, with a European super state exercising a new dominance from Brussels." This speech revol...

Like a broken clock, remainers are occasionally right. One example of this is the Irish border question which many leavers have ignored or dismissed for too long. While we don't believe this issue is as impossible to solve as remainers insist, it does require an appropriate amount of attention. So far, different proposals have been suggested to avo...

Tuesday 20th March 2018, from 1pm - 3pm How the Brexit negotiations should be handled.The man who delivered the Estonian Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1991 to Mikhail Gorbachev, the Head of the Soviet Union, advises the UK on Brexit. Location: Committee Room 20The House of CommonsWestminster London SW1A 0AA(via the Cromwell Entran...

European Council President Donald Tusk has suggested Britons could have a "change of heart" about Brexit.Photograph: European People's Party, Wikimedia Commons In a recent speech to the European Parliament, European Council President Donald Tusk claimed that Brexit would become a reality unless Britons have a "change of heart". His words echo persi...

Ants Laaneots was commander of the Estonian Defence Forces and is now a member of the Riigikogu, the Estonian Parliament. Theresa May's visit to Poland just before Christmas reminded us of the big realities of Brexit and the EU, realities which are often strenuously ignored.Some of the reporting has, maybe, been wishful of an adoption by HMG of a m...

It's been one and a half years since Brexit was confirmed by the British vote, but only now are we really seeing the true colours of the bill. While Brexit is predicted to cause a stir in many industries, including trade and even flight, there are now apparent effects on the education system, although these appear both positive and negative. For st...

Brexit negotiations are underway, and the future of travel and working in the United Kingdom is a difficult and complex entity. There are numerous news sources and reports suggesting various different factors, and with this uncertainty, many people are left wondering about how they are going to travel to the UK in the future, on business and for pl...

Andrew Roberts asks you to support the Bruges Group Brexit is under threat. Every day an anti-democratic alliance orchestrated by Tony Blair, senior Labour figures, the Lib Dems, together with their cheerleaders in big business and the media, are working to block delivery of what you, I and 17.4 million others voted for on 23rd June 2016. Every day...

A gathering storm over London.Photograph: Garry Knight, Wikimedia Commons. While the UK's parliament debates the EU Withdrawal Bill, its government is pursuing a post-Brexit deal on the continent. On both fronts, the decision Britons took to leave the EU is under threat. Indeed, their government has precious little wiggle room to deliver, but it st...

The historic city of Bruges has long attracted some of the world's leaders, including Margaret Thatcher who made her famous Bruges speech at the College of Europe, which is still considered a political centre today. Bruges has so much to offer visitors, so here's why you should renew your e111 card, pack your suitcase and head to the charming city ...

Bruges Group ConferenceWill Britain make a Brexit deal with Brussels? What should the UK prioritise? Where should it draw the red lines? When is the cost of any deal too high? Will we get what we actually voted for? This conference will answer those important questions. Saturday, 4th November 2017 http://www.brugesgroup.com/events Conference traile...

Photograph: DG EMPL, Flickr

British Prime Minister Theresa May outlined her government’s vision for Brexit in a speech delivered in Florence on September 22. In a bid to breathe new life into ongoing UK-EU negotiations, she presented proposals regarding the rights of EU citizens living in the UK, the length of a “transition period” after 2019, and the sum Britain might pay during that period. Rather than inspiring counterproposals or constructive criticism from EU leaders, May’s speech generated little more than the same refrain repeated from Brussels since negotiations began: that more “clarity” was needed, and that “sufficient progress” would have to be made before talks could advance. This lacklustre, somewhat apathetic EU position does not look like the result of sincere consideration of May’s proposals, or a constructive attitude towards the talks. Rather, it looks a lot more like a deliberate tactic to either prevent Brexit, or punish Britain.

Some might find this approach perplexing. After all, is it not in both parties’ interests to negotiate a mutually-beneficial outcome? Not necessarily…

To better understand Brussels’ foot-dragging in Brexit talks, it helps to understand the incentives driving it. First and foremost, the EU is a political union. Economic, social, or environmental considerations may all have contributed to the appeal of ever-closer union, but they remain secondary to the very political objective of federal statehood. Indeed, from the days of Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman at the dawn of European integration, to more the more recent mandates of José Manuel Barroso, Viviane Reding, or Guy Verhofstadt, the goal of a pan-European nation state is no secret.

Grasping that European statehood is the EU’s ultimate objective is essential for the UK government’s Brexit Secretary David Davis and his team of negotiators as they engage with their counterparts. It means that, no matter how amenable the UK is to facilitating trade or subsidizing the EU’s budget, the bottom line in Brussels remains the preservation of their political project. The win-win economic gains desired by the UK are not necessarily desired by the EU, for whom a successful Britain would signal there is no longer any economic appeal to remaining in the bloc. A strong UK economy poses an existential threat to European integration.

This explains why trade negotiations have not even begun, despite both parties already sharing near-identical norms and regulations. It is also why the EU seems in no rush to maintain access to the UK’s large consumer market, with Britons buying more from the EU than the other way around. In order to preserve the union, the EU’s only options are to ensure the UK remains inside, or fails outside.

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Title" tag="h3" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Supporting Bombardier - Putting employment in Britain at the heart of economic policy.[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Robert Oulds[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h5" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]25th September 2017[/pb_heading][pb_divider el_title="Divider 1" div_margin_bottom="30" div_border_width="2" div_border_style="solid" div_border_color="#0151a1" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_divider][/pb_column][/pb_row][pb_row ][pb_column span="span3"][pb_image el_title="Article Image if required DELETE Column if not required" image_file="images/0916cseries.jpg" image_alt="Type text for SEO (example Bruges Group : Image Title)" image_size="fullsize" link_type="no_link" image_container_style="no-styling" image_alignment="inherit" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_image][pb_button el_title="PDF Link : Delete this component if it is not required 2" button_text="Lobby your MP to help" link_type="url" button_type_url="http://www.brugesgroup.co.uk/lobby.php" open_in="new_browser" button_alignment="inherit" button_size="btn-sm" button_color="btn-primary" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_button][pb_button el_title="PDF Link : Delete this component if it is not required 2 3" button_text="Government help? Vote online" link_type="url" button_type_url="/media-centre/polls" open_in="new_browser" button_alignment="inherit" button_size="btn-sm" button_color="btn-success" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_button][/pb_column][pb_column span="span9"][pb_text el_title="Article Text" width_unit="%" enable_dropcap="no" appearing_animation="0" ]

We are determined that Brexit, if when it eventually happens in earnest, delivers the change we need. One of these new approaches can be in defending British industry, along with its jobs and innovation from unfair actions. But why wait for Brexit? It can begin now!

Bombardier, a major employer in Britain, a new entrant in the plane market, is being threatened by a trade complaint brought by Boeing designed to keep it out of the US market.[i] Theresa May’s government must show that a post-Brexit Britain will use its new-found independence to stand up for UK jobs. A policy area where we would not have to live with pan-EU rules any more. British taxpayers give Boeing hundreds of millions of pounds in defence deals, while at the same time they’re trying to close British factories. That’s not the action of a trusted partner for this country.

“People have only as much liberty as they have the intelligence to want and the courage to take.” ― Emma Goldman The name of a quiet medieval town in Hungary – Visegrad – has in recent times become synonymous with the word “rebellion” in Brussels. The Visegrad Group, also known as the Visegrad Four, or V4, is a cultural and political allianc...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]All that is required is to exempt any fisheries acquis from the withdrawal bill.[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h4" text_align...

This country's change from consuming sugar derived from sugar cane, which Britain historically purchased from its old colonial territories, to consuming sugar extracted from sugar beets from about 1973 onwards has slowly but surely greatly contributed to this country's obesity problem S Davies 2nd September 2017 I pose the question of w...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]This country’s change from consuming sugar derived from sugar cane, which Britain historically purchased from its old colonial territories, to consuming sugar extracted from sugar beets from about 1973 onwards has slowly but surely greatly contributed to this country’s obesity problem[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]S Davies[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h5" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]2nd September 2017[/pb_heading][pb_divider el_title="Divider 1" div_margin_bottom="30" div_border_width="2" div_border_style="solid" div_border_color="#0151a1" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_divider][/pb_column][/pb_row][pb_row ][pb_column span="span3"][pb_image el_title="Article Image if required DELETE Column if not required" image_file="images/euobesityhelmutkohl.jpg" image_alt="Type text for SEO (example Bruges Group : Image Title)" image_size="fullsize" link_type="no_link" image_container_style="no-styling" image_alignment="inherit" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_image][/pb_column][pb_column span="span9"][pb_text el_title="Article Text" width_unit="%" enable_dropcap="no" appearing_animation="0" ]I pose the question of whether this country’s change from consuming sugar derived from sugar cane, which Britain historically purchased from its old colonial territories, to consuming sugar extracted from sugar beets from about 1973 onwards has slowly but surely greatly contributed to this country’s obesity problem. It is popularly believed that despite us as a nation consuming fewer calories these days than was the case in the 1960's, obesity has gradually become a real problem. So, is it the EU's forced substitution of sugar obtained from sugar beets rather than sugar obtained from sugar cane making us really fat?

I suggest that the country's obesity pandemic is partly due to its switch to the creation of sugar from sugar beets, which came about after the UK entered the European Economic Community in 1973. The UK had historically relied upon sugar cane for its sugar, which was a state of affairs that hadn't changed since sugar was first introduced into this country and became more widely available from about the 16th - 17th centuries onwards. In fact beets were not discovered as an alternative to cane until the late 18th century and weren't used in manufacturing until the early 19th century, when they had to be cultivated to yield a higher sucrose content than that which they originally and naturally contained.

The difference in quality between the two types of table sugars is a matter of debate. From a culinary perspective, I personally find sugar derived from sugar cane to be a far superior substance. I find it crisper and that it gives a lighter result. There is no apparent taste to cane sugar, which is just sweet. I personally find that there is an ever so slight aftertaste or noticeable different texture to beet sugar. Cane sugar is the master baker's sugar of choice, whatever the chemists say about it supposing to be the same. Meringues made from sugar cane are crisper and far superior. Cakes don't flop as easily with cane sugar. Yet the scientists say that “sugar is just sugar” and that there is no difference between the two substances.

So, what is the difference between sugar cane and sugar beets? To look at a 500 gram pack of Silver Spoon (beet sugar) and Tate & Lyle (cane sugar) next to each other, they generally appear to be of the same size, and have the same volume, so there can't be much of a difference regarding the physical density of the product. On closer inspection of the sugar grain or crystals, the beet sugar may seem less crisp and light than the cane sugar. However, I think that to appreciate the difference between them, one needs to look at how the two products are processed, the difference in production being necessary due to their respective botanical composition.

Sugar beets and sugar cane must be processed differently to achieve apparently the same table sugar. Sugar beets, which are a root crop, are sliced and boiled to extract the syrup. This is then evaporated into crystals. Sugar beets produce two by-products: the beet pulp, from which the sucrose syrup has been extracted, and molasses. The beet pulp is dried into pellets and fed into the human food chain inasmuch as it's then sold on as animal feed. The sugar beet molasses is not fit for human consumption but can and is fed to animals.

Sugar cane, which grows in reeds above the earth's surface for several feet before it's harvested, is sliced and heated in water to extract the sugar syrup. Cane sugar also produces molasses as a by-product. However, this molasses can be used for human consumption - e.g. in the Caribbean it is utilised in the manufacture of rum. The bark or reeds of the sugar cane crop is then either defunct or can be used in the manufacture of baskets and mats etc.

The botanical composition of sugar beets is described on Wikipedia as follows: "The pulp, insoluble in water and mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin, is used in animal feed." The botanical composition of sugar cane is described as: "A mature stalk is typically composed of 11–16% fiber, 12–16% soluble sugars, 2–3% nonsugars, and 63–73% water."

I suggest below that the more resinous nature of sugar beet may have a deleterious effect on the human liver. It must be ground down or processed to such a level in standard sugar production that it is then able to permeate the small intestines and enter the liver via the bloodstream. This can then act as a resinous mist on liver cells and affect their ability to act to their required capacity, so forcing the body to rely on alternative glucose-fuelling sources - i.e. cortisol from the adrenal glands. Perhaps cane sugar, having no inherent resinous qualities, degrades more easily, leaves no residue and is thus less taxing on the human body.

In attempting to explain my theory, I think that it's important to first go through the stages involved in the body's metabolism of food. The human body, and animal kingdom in general, are glucose-driven vessels who rely upon glucose as their primary source of fuel. This contrasts with the plant kingdom, whose primary source of energy is slightly different and is called fructose. This general blood sugar requirement is irrespective of whether the body ingests fat, carbohydrate or protein.

I initially wondered whether it was fructose, which, as has been noted above, is not the animal kingdom's source of sugar. As a substance, it may impose a bit of a strain on the body because it is not broken down by insulin, as glucose is, and in the usual way. It must be processed in the liver after ingestion, before it's released into the wider bloodstream. It has been suggested that everyone is slightly fructose intolerant, with their ability to break down fructose varying in degree from individual to individual and associations have been made between fructose and fatty liver disease. However, my point here is that where one obtains the fructose or plain sugar from also makes a difference – i.e. whether it’s obtained from sugar beet or sugar cane.

In fuelling the human body, it is of paramount importance to maintain blood glucose homeostasis - i.e. balance - and therefore blood glucose levels hover within a limited range, with a normal range being 70 to 110 mg/dl (milligrams per deciliter). The body will try and move heaven and earth to achieve this balance and therefore has more than one mechanism to ensure blood glucose stability. For immediate use, it will rely on the glucose stored in the liver. This is termed glycogen. Thereafter, glucose is stored in fat and muscle tissues.

The body accesses glucose by synthesizing (i.e. creating) and using insulin, which is a hormone produced by the beta cells of the pancreas. Insulin mobilises blood glucose and ensures it reaches the body's cells and muscles. The pancreas also synthesizes another hormone called glucagon, which is something of a mirror-image to insulin. Glucagon senses when blood glucose levels are low and sends negative feedback messages to the liver that this is the case, so instructing the liver to release more glucose, whilst insulin mops up glucose in the bloodstream and either helps the body utilise it immediately or helps to store it as excess fat.

If glucose or glycogen stores in the liver are low, the body can also produce a hormone called cortisol from the adrenal glands, which lie on top of the kidneys, to remedy the shortfall. However, the body's usual glucose reserves are stored in the liver. If the body is forced to rely on short-term cortisol from the adrenals to release glucose stores from the body’s tissues, this is not the preferred method and long-term use carries its own problems - e.g. high blood pressure, which is associated with an increased cardio-vascular risk, increased risk of stroke, increased risk of diabetes due to cortisol's glucose-raising effects. Cortisol is also associated with obesity because it slows down the body’s rate and generally deteriorates body tissue etc.

So, why would the body choose to use the cortisol hormone instead of the glucagon one?

Simply because it feels that it has to, to maintain blood glucose balance. Either the alpha cells of the pancreas, which produce glucagon, have become impaired, or the liver's reading of and sensitivity to them has become impaired. The body is then moved into emergency mode and cortisol is forced to take over and aid the release of glucose into the bloodstream where glucagon left off. So, we need to ask ourselves whether the liver cells or even the pancreas cells are being caked up with a resinous substance that hinders its ability to detect blood glucose levels and whether this irritating substance is present in sugar beet.

By S Davies

[/pb_text][/pb_column][/pb_row]

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]A Brexit-driven reconfiguration of the UK’s food and agricultural sector suggests that a period of significant transformation lies ahead; but if mapped...

Brexit could hit UK travellers like a summer storm. But don’t fret – it’s not all bad. Although it is deemed likely that travellers will needs a visa to travel around Europe, mobile roaming data charges are set to be scrapped entirely across the board. If you plan on travelling around Europe this summer, make sure you apply for an E111 card ...

With the Brexit negotiations in full flow, Britain is looking for a way to make the transition away from the European Union run as smoothly as possible while ensuring that Brexit happens unimpeded. There are two possible exits. The first is a clean cut that will come into effect on 29th March 2019. The second option is to negotiate a transit...

Barely one year after the Brexit referendum, and under four months since the triggering of Article 50, the Financial Times has published a “democratic case for stopping Brexit”, adding to a crescendo in overt calls to upend the exit process. How did we get here? The whole point of the EU referendum, just like the Scottish referendum bef...

The Union Jack flies over the Houses of Parliament in Westminster.Photograph: Rian (Ree) Saunders, Flickr With Article 50 triggered and Brexit negotiations well underway, the UK government looks like it’s carrying out the instructions it received from 17.4 million voters last summer. At best, Britain and the continent will establish a mutuall...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Unlocking the benefits of leaving the EU[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title 3" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]A Brexit-driven reconfiguration of the UK’s food and agricultural sector suggests that a period of significant transformation lies ahead; but if mapped successfully, can be a positive one.[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Richard Ferguson[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Article Title 3" tag="h5" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]21st June 2017[/pb_heading][pb_divider el_title="Divider 1" div_margin_bottom="30" div_border_width="2" div_border_style="solid" div_border_color="#0151a1" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_divider][/pb_column][/pb_row][pb_row ][pb_column span="span3"][pb_image el_title="Article Image if required DELETE Column if not required" image_file="images/capcommonagriculturalpolicy.jpg" image_alt="Type text for SEO (example Bruges Group : Image Title)" image_size="fullsize" link_type="no_link" image_container_style="no-styling" image_alignment="inherit" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_image][pb_button el_title="PDF Link : Delete this component if it is not required 2" button_text="Read the full research online" link_type="url" button_type_url="/images/papers/thefutureisanothercountry.pdf" open_in="new_browser" button_alignment="inherit" button_size="btn-sm" button_color="btn-primary" appearing_animation="0" ][/pb_button][/pb_column][pb_column span="span9"][pb_text el_title="Article Text" width_unit="%" enable_dropcap="no" appearing_animation="0" ]

The possibility of a Brexit-driven reconfiguration of the UK’s food and agricultural sector suggests that a period of significant transformation and structural adjustment lies ahead. Set against an industry already in the midst of rapid technological displacement, value-chain disruption and regulatory change, a transformative event such as Brexit appears to add to existing uncertainty.

However, while the potential institutional, financial and operating frameworks that will arise from Brexit suggest a wide range of possible outcomes, the process, if mapped successfully, can be a positive one. The UK’s current position is not unique. In the 1980s, the government of New Zealand instigated a reform programme to transform the country’s food and agriculture sector, the results of which were immediate and painful as well as long-term and beneficial.

At the core of the transformation that shook New Zealand’s agriculture sector in the 1980s and 1990s was a pressing need to access new markets in the face of external economic shocks and structural adjustments, such as the UK’s decision to join the then European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973. While there are obvious direct parallels between the New Zealand case study and Brexit, both situations remain distinct and unique. The first section of this report “The past is another country” considers the New Zealand experience and argues that an agenda focused on long-term goals can deliver significant economic and social benefits, but may come with considerable short-term costs. The battle about to commence is set to be as brutal, complex and ideological as that which determined the direction of the British economy in the late-1970s and early 1980s.

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Dominic Grieve, the Conservative Chairman of the Commons Intelligence and Security Committee, argues that the UK must retain membership of the EU’s...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]How a compromise agreement may keep Britain subject to aspects of the EU.[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Date" tag="h5" text_align="inherit" fon...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]The UK should not seek full Europol membership or participation in the flawed European Arrest Warrant scheme.[/pb_heading][pb_heading el_title="Dat...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Memorandums of Understanding, or exchange of notes/letters, can form a key part of the necessary transitional arrangements as the UK moves from bei...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Technology is driving changes that remote bureaucrats have yet to imagine. Brexit is about openness. It’s about people realising their global role ...

[pb_row ][pb_column span="span12"][pb_heading el_title="Article Sub Title" tag="h4" text_align="inherit" font="inherit" border_bottom_style="solid" border_bottom_color="#000000" appearing_animation="0" ]Last month, an event occurred which got little fanfare, but is likely to have a significant effect on the future of the UK, especially after Brexit...

Contact us

246 Linen Hall, 162-168 Regent Street

London W1B 5TB

Director : Robert Oulds MA, FRSA

Founder Chairman : Lord Harris of High Cross